|

Reiner Torheit

|

|

« on: 10:05:54, 14-12-2007 » |

|

r3ok boarder Colin Holter has written an interesting piece about "what New Music is" on NewMusicBox, which I recommend to others: http://www.newmusicbox.org/chatter/chatter.nmbx?id=5369Discussion of the mterial in the article is very welcome  , but I would appreciate this notturning into (yet) another jibe-chanting diatribe against new music... there are already existing threads where you can post that kind of stuff. Thanks. , but I would appreciate this notturning into (yet) another jibe-chanting diatribe against new music... there are already existing threads where you can post that kind of stuff. Thanks. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

"I was, for several months, mutely in love with a coloratura soprano, who seemed to me to have wafted straight from Paradise to the stage of the Odessa Opera-House"

- Leon Trotsky, "My Life"

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #1 on: 00:07:29, 16-12-2007 » |

|

I suspect the thing which will always militate against Schoenberg getting the same kind of acceptance Bartók gets (the main dichotomy in Colin Holter's article) is that Schonberg's forms are very seldom as clear as Bartók's, however fine the material might be. So even though the material is often both very fine and very digestible at any given moment the pieces themselves remain tough going for the listener. This listener, anyway...

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Andy D

|

|

« Reply #2 on: 00:35:54, 16-12-2007 » |

|

From my point of view, trying to "define" what's new music and what's old is just as pointless as trying to define what's music and what isn't and for the same reasons as I gave on that thread.

spnm used to have a seemingly arbitrary dividing line in their new notes magazine of 1960 (they might still do but I don't get it any more) - but "arbitrary" is the important word.

To be rather pedantic, I reserve the term "new music" for something that has been written recently (although I don't define any cut-off point wrt "recently").

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #3 on: 00:51:30, 16-12-2007 » |

|

I went through my Stockhausen ipod tracks today changing the 'Avant-garde' tag to 'Classical'. Completely meaningless I know.  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

richard barrett

|

|

« Reply #4 on: 01:09:41, 16-12-2007 » |

|

I wonder when the term "new music" first began to be used. My guess would be in the 1950s. At that time I think there was felt to be a fairly clear historical/philosophical dividing line between what the "post-Webern" people were doing (not least in terms of the new technology some of them were using) and everyone else. Subsequently this line has become gradually less clear, and nowadays my inclination would be to stop pretending that it exists at all. The problem with using the term just for "recent" music is that the words "new music" still come with some of their 1950s baggage: the phrase has been "used up". I think some people still feel a need to draw the aforementioned line, and argue about where it's situated, often to mark themselves or those they admire off as special in some way, but I feel this is wishful thinking.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sydney Grew

Guest

|

|

« Reply #6 on: 01:19:33, 16-12-2007 » |

|

Many years ago Schoenberg's music was bracketed together with that of Hindemith (as well as with that of Bartok). Yet to-day Hindemith is seldom mentioned in the same breath; this is probably because people have reached a clearer discernment of what Schoenberg was doing (or at least attempting to do).

Most people we think have a division in their mind between on the one hand music whose procedures are so well known that listening to it can be almost too easy and familiar an experience, and on the other hand music whose procedures are so little known that listening to it is a considerable and not always pleasant effort. (In some cases the effort may be a worthwhile investment, but not in all.)

The location of this division in the repertoire varies between individual persons, but (and this is perhaps our principal point) it is always quite a sudden and sharp division.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Baz

Guest

|

|

« Reply #7 on: 09:50:55, 16-12-2007 » |

|

I wonder when the term "new music" first began to be used. My guess would be in the 1950s. Not forgetting for example 'Ars nova' (c. 1320), and Nuove Musiche (Caccini, 1602) At that time I think there was felt to be a fairly clear historical/philosophical dividing line between what the "post-Webern" people were doing (not least in terms of the new technology some of them were using) and everyone else. Subsequently this line has become gradually less clear, and nowadays my inclination would be to stop pretending that it exists at all. The problem with using the term just for "recent" music is that the words "new music" still come with some of their 1950s baggage: the phrase has been "used up". I think some people still feel a need to draw the aforementioned line, and argue about where it's situated, often to mark themselves or those they admire off as special in some way, but I feel this is wishful thinking.

The word "new" had (I remember from the 1950s onwards, and still to some extent today) the almost mystical connotation of "better". This was (and still is) a catchword in advertising (e.g. "New, improved Daz for whiter washes" - the use of the word "new" implying improvement or superior quality, perhaps linking psychologically with the idea that a new car is better than an old one). Perhaps we should no longer worry about the point at which the new becomes relegated to the old. As far as newness is concerned, when a living composer's music is billed as (say) a 'First Performance', we can understand that - in terms of chronology - it is 'new'. But it is not necessarily true to believe that this newness is its real novelty, or that as its newness wears off over time its artistic worth will diminish. Some music marketed as 'new' rests its case for merit upon this slogan, but as it ages so does its perceived merit. Other music remains as it always was, and the novelty of 'newness' is eventually seen only as an historical pointer that is incidental to its actual merits. Perhaps the simple term 'music' should suffice on the assumption that listeners - like composers - are quite able to exercise a modicum of intelligence. Baz |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #8 on: 11:05:51, 16-12-2007 » |

|

As far as newness is concerned, when a living composer's music is billed as (say) a 'First Performance', we can understand that - in terms of chronology - it is 'new'. I know it's a trivial point of logic but for some reason it's often hard to get into one's head (it is for me anyway!) the fact that every single piece of music ever written was new at the time. So newness in the chronological sense isn't just something that a tiny little subset of music has had, it's a basic property of all music... ("So what exactly are you trying to say here, Ollie?" "Actually I'm not sure...") |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

time_is_now

|

|

« Reply #9 on: 18:55:13, 17-12-2007 » |

|

I wonder when the term "new music" first began to be used. My guess would be in the 1950s. Well, Adorno already used it in the title of a book in 1949, Philosophie der neuen Musik. Ollie may not be sure what he's trying to say but he's still on to a couple of things (IMHO and all that) - one thing being that yes, it is easy to forget that everything was new once (in the same way that people forget Brahms didn't always have that beard); another thing being that 'new' can have more specific meanings, whereby not everything is equally new. I think this is what I'd like Colin to have addressed a bit more in his article ... 'New music' to me has never meant the same as 'recent music'. Indeed, to call something 'new music' to me still signals some of the sort of aesthetic concerns which Adorno had in mind in titling his book as I mentioned above (and which were lost when it was translated as 'Philosophy of modern music', which has a somewhat different nuance). Also, when Adorno picked up the term again in the early 1960s to write a polemic against some of the younger Darmstadt composers, a polemic which he titled 'New music is growing old' ('Das Ältern der neuen Musik'). Of course, he wasn't talking about pieces becoming less recent, but suggesting that even the most recent pieces no longer had the quality of 'newness' which had characterised, say, some of Schoenberg's music. I think Adorno would also have argued that genuinely 'new' music remains new forever, or at least for a long time. It's not a relative term. I'm not saying Adorno's is the only possible view of the situation, by the way - just pointing out one example of a different kind of use of the designation 'new'. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

The city is a process which always veers away from the form envisaged and desired, ... whose revenge upon its architects and planners undoes every dream of mastery. It is [also] one of the sites where Dasein is assigned the impossible task of putting right what can never be put right. - Rob Lapsley

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #10 on: 02:11:50, 18-12-2007 » |

|

At one point that essay of Adorno was translated under the title 'Modern Music is Getting Old', which considerably dampens the implicit irony of Adorno's original title. Incidentally, Heinz-Klaus Metzger wrote a retort to Adorno's essay, entited 'Das Altern der Philosophie der Neuen Musik', in 1957 ('Das Altern der Neuen Musik' was from 1955, not the 1960s, and is generally thought to have been inspired by hearing Karol Goeyvaerts's Nummer 1: Sonata for two pianos, which Goeyvaerts had performed part of together with Stockhausen in Darmstadt in 1951, in Adorno's presence - Zagorski (see below) contests the centrality of this work in influencing Adorno's conception, however) and in 1962 a further essay called 'Das Altern der jüngsten Musik', in which he talks about Messiaen, Boulez, Nono and Stockhausen (both are included in the volume Musik wozu: Literatur zu Noten, edited Rainer Riehn (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1980)). Adorno and Metzger took part jointly in a radio debate in 1957-58 entitled 'Recent Music - Progress or Regression' (I'm not sure of the German title of this - it's referenced in Stefan Müller-Doohm's biography of Adorno (translated Rodney Livingstone, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2005)), and in a much later interview with Hans-Klaus Jungheinrich, Metzger pointed out that Adorno's response to his retort was not at all hostile, but they actually became friends as a result. Metzger also said that 'With hindsight, Adorno's view turned out to be prophetic' (the full interview is included in Jungheinrich (ed), Nicht versöhnt: Musikästhetik nach Adorno (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1987)).

Adorno did capitalize 'Neuen Musik' in the essay (both for the title and on subsequent appearances of the term within the text - at least it appears that way in Dissonanzen, as included in Vol. 14 of the Gesammelte Schriften), though not in Philosophie der neuen Musik, nor in various other essays also including 'neue(n) Musik' in the title - so perhaps there was some significant emphasis on the word 'new' in this particular context as distinct from others.

(see also Marcus Zagorski, 'Nach dem Weltuntergang: Adorno's Engagement with Postwar Music', in The Journal of Musicology, Vol. 22 Issue 4 (2005), pp. 680-701, for more on this subject. All rather tangential to the thread, I know, but some might find it interesting nonetheless)

|

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 02:59:11, 18-12-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Sydney Grew

Guest

|

|

« Reply #11 on: 11:23:55, 18-12-2007 » |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

John W

|

|

« Reply #12 on: 19:09:11, 18-12-2007 » |

|

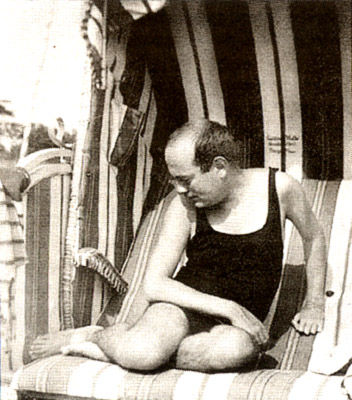

Eh? funnyface That face is far from 'funny' here in the UK, Grew, many many people look like this and never make me laugh, in fact my own appearance may soon approach closely to it and that definitely won't be funny, to me anyway. |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 20:41:03, 18-12-2007 by John W »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #13 on: 19:29:15, 18-12-2007 » |

|

I believe that to be the face of one Theodor W. Adorno, John. He probably wouldn't make you laugh either.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #14 on: 20:03:01, 18-12-2007 » |

|

Although it depends how easily amused you are.  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|