|

stuart macrae

|

|

« Reply #150 on: 13:10:15, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Any idea why there's not been a new Composer-in-Association, Stuart? (In a roundabout way this is a sort of attempt to get back on-topic!)

Sorry, no idea..... |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #151 on: 13:19:27, 03-05-2007 » |

|

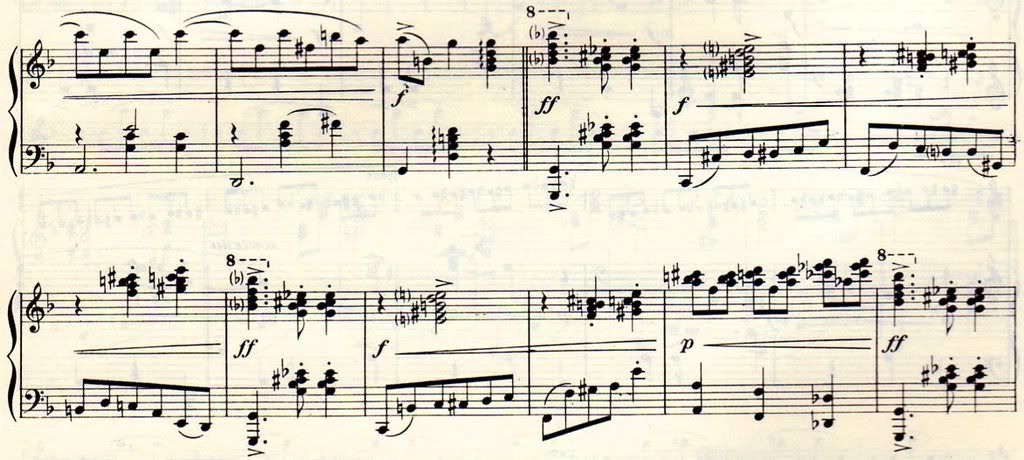

Not actually what I was talking about - I'm talking about having conceived his orchestral music in piano terms, not the other way around. There are several passages in La Valse which don't work in orchestral performance because the orchestral bass line is less able to dominate the texture than a bass line on the piano can do. Figure 36 is the obvious spot. That's assuming that Ravel wanted the orchestral bass line to dominate. Here is Figure 36 in Ravel's piano transcription (after the double bar):  In the orchestral version (which can be downloaded for free at http://www.imslp.org/wiki/Valse%2C_La_%28Ravel%2C_Maurice%29 ), the bass line (from the second bar after Fig. 36) is played by clarinets, bass clarinets, violas and cellos, joined in the seventh bar after Fig. 36 by oboes and second violins. The bass trombone, tuba and double basses add punctuation. The chords, on the other hand, are played by violins and full brass - horns, trumpets and trombones, which is obviously going to produce a more prominent sound. Ravel knew what he was doing orchestrally, he could easily have used only a subset of the brass to balance the lines more. But much of the piece, at least as I hear it, makes use of a certain unusual relationships between parts (some deliberately top-heavy and overblown), which adds to its grotesque quality (he cited approvingly the fact that some critics 'situate this dance in Paris, on a volcano, about 1870, others, in Vienna, before a buffet, in 1919'). The balance changes in lots of directions; I reckon if Ravel had wanted this section to be bass-dominated, he would have modified the orchestration. By the eighth bar of Fig. 38, in the orchestral version, the lines fuse into this terrifying build up of chords in the whole orchestra (all strings, flutes, horns and trumpets playing triplet repeated groups, the rest of the orchestra backing these with chords on the crotchets). Ravel's piano equivalent of this is a very poor substitute (indeed this is true of many of the long crescendos in the work, let alone the climax). A fair amount of his other orchestral music was originally written for piano (though even there I sometimes detect orchestral thinking, see the example below from the Valses Nobles et Sentimentales for example), but La Valse seems as thoroughly conceived in orchestral terms as anything he wrote. The piano version was (according to Roy Howat) only really conceived for domestic use or ballet rehearsals.  |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 13:21:18, 03-05-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #152 on: 13:25:15, 03-05-2007 » |

|

if I practised it every day for a week Hm, yes. The Lever du jour from Daphnis and Chloé springs unbidden to mind. Thing is of course, orchestral players (and for that matter players in specialist new music ensembles) often don't need composers to make them feel insecure. Sometimes it's their default setting. One of the important things in writing for orchestras or ensembles or anyone is somehow to work out what won't work the first few times it's played but will or might come off after a bit of work and be all the more effective for it. Birtwistle revised Earth Dances around 2000-2001 or so; one of the things which happened in the revision was that all those characteristically 'Birtwistlean' unbeamed demisemiquavers became beamed semiquavers. Doubtless his thinking was that it wouldn't matter; to me it really does sound different, with just the tiniest hint of being phrased in 4s or at least 2s. (The EM Orchestra recording is of the new version.) I had a case recently where a composer had removed something from a bass clarinet part after the original performer found it impossible or at least not effective; I lost my music between performances and ended up with the unrevised version for the next concert where we played it. Sure enough the composer preferred it and that's the way I play it now. It's a bugler of a question to know what to revise out and what to leave... I very much applaud composers with the guts to take the long view as long as it's not entirely unencumbered by reason.  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #153 on: 13:33:26, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Ravel knew what he was doing orchestrally, he could easily have used only a subset of the brass to balance the lines more. Or he could, for example, have marked the bass line f with a crescendo to ff and the chords fp and mf if he'd wanted the chords less prominent than the bass line. Oh look, indeed he did. Both at 36 and at 63. I think you'll find the bassoons and contra are also on the bass line. In other words everything he could throw on it, if you assume he didn't regard the tuba as capable of playing it cleanly. |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 13:36:41, 03-05-2007 by oliver sudden »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #154 on: 13:41:19, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Ravel knew what he was doing orchestrally, he could easily have used only a subset of the brass to balance the lines more. Or he could, for example, have marked the bass line f with a crescendo to ff and the chords fp and mf if he'd wanted the chords less prominent than the bass line. In full knowledge of what the result would sound like (having already composed and heard performed a fair amount of orchestral music by this stage). As brilliant an orchestrator as Ravel understood the prominence of a brass chord even when it had gone down to piano, and the writhing quality of the bass when trying to compete with this (much of this tension is lost when played on the piano), eventually subsumed into the tutti crescendo in the eighth bar of the section. Using only two rather than all four of the horns (the parts are simply doubled), or using more woodwind rather than brass, would have been an easy option to lessen the burden of the treble. |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 13:44:18, 03-05-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #155 on: 13:46:13, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Yes, well that's obviously your point of view and you're quite entitled to it. Personally I don't regard it as supported by the score but there we are. I look forward to your performance.

21st century anyone?

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

richard barrett

Guest

|

|

« Reply #156 on: 14:13:12, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Whether Ravel's orchestration was or wasn't influenced by writing at the piano (and, in my opinion, how could it not have been?), it was certainly conditioned by the same attitudes towards registral and timbral layout which made the piano of that time (and this) what it is.

Yes, the 21st century. So: there's a problem with the composition of an orchestra reflecting the priorities of present-day composers should they wish not to take the aformentioned attitudes as read, and, for reasons I don't need to underline, this is unlikely to be possible to address by adding more instruments except in a small way, so the alternatives are either to leave instruments out or to deploy them in a different way. Or, of course, to avoid writing for orchestra altogether.

With regard to the "long view" mentioned earlier by Ollie, I would see it like this: one isn't "writing for posterity" but for an optimised version of the present, the alternative to which, in my view, is to contribute to a general sense of cynicism and stagnation. I'd prefer to be living in a world where a third-desk violinist had the time and encouragement to practice their part "every day for a week" and I feel that caving in to the prevailing (and indeed quite understandable) apathy isn't going to bring us any closer to that world, and putting into practice the vision of and desire for that world is more important to me than what this or that player at a particular place and time might be thinking.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #157 on: 14:28:53, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Whether Ravel's orchestration was or wasn't influenced by writing at the piano (and, in my opinion, how could it not have been?), it was certainly conditioned by the same attitudes towards registral and timbral layout which made the piano of that time (and this) what it is. Well, I don't see how that applies at the big climax at Fig. 95, with those ominous crescendos on sustained notes in the central register that engulf the melody (in the piano version, all he can do is a rather pathetic upwards arpeggio as a substitute). More a case, throughout that piece, of a somewhat detached and ironised perspective on Wagnerian orchestration. The shrieking high chromatic lines would sound merely brilliant on the piano, and the ascending string figurations in chords merely clumsy (as they do in the transcription - some of the pitches he simply notates with small noteheads, indicating their impracticality) without doing so in a meaningful way. The piece contains one of the most brilliant and wholly individual pieces of orchestration I know of. There is an aesthetic of orchestral clarity (in terms of individual parts), inherited from Stravinsky and which has been hugely influential through the 20th century and into the 21st, which is often applied to Ravel's music; to my ears it rather obliterates the romantic element (sometimes more murky, brooding, etc.) which co-exists with his more detached sensibility. There's still a lot of potential in that approach to the medium. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

richard barrett

Guest

|

|

« Reply #158 on: 14:32:51, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Oh-oh, Stravinsky's been mentioned - only one small logical step to go and you'll have this thread where you want it, Ian!  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #159 on: 14:46:18, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Oh-oh, Stravinsky's been mentioned - only one small logical step to go and you'll have this thread where you want it, Ian!  If you're just trying to bait, I'm not biting. Do you think a Stravinskian aesthetic of orchestral writing (in terms of its broad essentials) provides the best model for the 21st century? It took me a while to come to terms with James Dillon's writing for orchestra, which uses a certain blurring of textures and so on as an expressive device (parts half-submerged and so on), now I realise I was listening to it too much from a post-Stravinskian viewpoint. With Dusapin's orchestral music, on the other hand, I often feel the 'blended' approach is taken too far and some more individuation of lines in performance would help lift the writing from what can become rather homogenous. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

time_is_now

|

|

« Reply #160 on: 15:20:55, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Do you think a Stravinskian aesthetic of orchestral writing (in terms of its broad essentials) provides the best model for the 21st century? No. I've always been puzzled by the supposed centrality of the Stravinskian aesthetic (or its caricature) to subsequent music ... |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

The city is a process which always veers away from the form envisaged and desired, ... whose revenge upon its architects and planners undoes every dream of mastery. It is [also] one of the sites where Dasein is assigned the impossible task of putting right what can never be put right. - Rob Lapsley

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #161 on: 15:32:02, 03-05-2007 » |

|

Well, I hear that sensibility at play in the orchestral music of Boulez, Stockhausen, Carter, Lachenmann, Donatoni, Birtwistle, Knussen, Ades, and countless others. There are major exceptions, of course - Xenakis to an extent, Scelsi, Sciarrino, Dillon, for example, but the Stravinskian approach (most of all in terms of clear delineation of parts, and relatively clear and distinct colouration) seems dominant. It seems to have rubbed off on players as well, when they complain about whether a particular line can be 'heard' individually or not.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #162 on: 15:40:11, 03-05-2007 » |

|

the Stravinskian approach (most of all in terms of clear delineation of parts, and relatively clear and distinct colouration) seems dominant. It seems to have rubbed off on players as well, when they complain about whether a particular line can be 'heard' individually or not.

Which I suppose leaves only two questions: why those qualities necessarily make a piece or an approach to the orchestra 'Stravinskian', and why it should be particularly 'Stravinskian' for a player to want their work to be heard. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #163 on: 15:48:21, 03-05-2007 » |

|

the Stravinskian approach (most of all in terms of clear delineation of parts, and relatively clear and distinct colouration) seems dominant. It seems to have rubbed off on players as well, when they complain about whether a particular line can be 'heard' individually or not.

Which I suppose leaves only two questions: why those qualities necessarily make a piece or an approach to the orchestra 'Stravinskian', Mostly because Stravinsky was the pioneer of such an approach with a large orchestra. and why it should be particularly 'Stravinskian' for a player to want their work to be heard. The key word omitted is 'individually'. Sometimes individual lines cannot be heard, but the total effect of their combination would be quite different without them. Was it Richard Strauss who, when challenged in this manner, said something about how he couldn't necessarily hear that particular part, but he would be able to hear if it wasn't there? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

richard barrett

Guest

|

|

« Reply #164 on: 15:48:52, 03-05-2007 » |

|

For what it's worth, I don't think Stravinsky's music is particularly central to any tendency towards contrapuntal clarity in 20th century music. Mahler's textures are just as lucid as Stravinsky and sound best when they're performed lucidly, which doesn't in any way mean performed as if they were by Stravinsky. (I believe Mahler also wrote for large orchestras.) Also, textural clarity is highly important to Pierre Boulez, for example, who doesn't even rate Stravinsky's music particularly highly, and it was also important to his "avant-garde" colleagues, who might have raised an eyebrow even at the occasional lipservice Boulez has paid to performing Stravinsky.

(I'm not that fond of most Stravinsky myself as it happens.)

I think Dusapin's orchestral music suffers from more serious problems than too much blending, like (for this listener) a total lack of structural tension, indeed no character to the material that one might base such tension upon. I find it insufferably, almost unfeasibly dull - I have a few CDs of his larger-scale works, thinking each time there must be something I can get out of this... and every time it just goes in through one ear and out through the other (admittedly there isn't that much to impede its trajectory). I think I've given up trying now.

Someone who wrote very beautifully and idiosyncratically for the orchestra, with the utmost clarity and sharpness of detail but in a completely unStravinskian kind of way, by the way, was Roberto Gerhard, particularly in his symphonies.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|