|

Ian Pace

|

|

« on: 10:05:49, 09-04-2007 » |

|

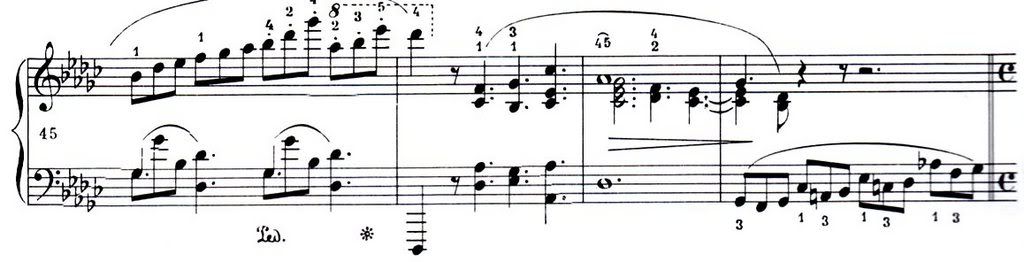

Ok, my starter for ten: It's reasonably well-known now that Chopin, in the context of his time, strongly adhered to a principle (and a mode of teaching) whereby counterpoint is seen to precede harmony, the latter emerging as a by-product of the former. In this he was very much at odds with the new approaches of the time pioneered at the Paris Conservatoire, where the situation was reversed; Berlioz's music demonstrates this tendency (also to do with the fact that he was a guitarist rather than pianist, so more liable to think in terms of chords rather than lines). Anyhow, to me this not only accounts for the Bachian contrapuntal sophistication of Chopin's music (so often lost when played in an overly melody-dominated way), but also the vocal (rather than orchestral) quality of his piano writing. But a passage which always interests me is that below, from the Impromptu in G-flat Op. 51:  The edition used here is the Paderewski, which is now found very problematic; in the notes at the back it points out that the original editions have a crescendo at the beginning of bars 33 and 34, but all subsequent ones have the diminuendo. Which of these is employed significantly affects the musical sense: if a crescendo, then the dynamic envelope underlines the progression towards the A-flat minor near-resolution, as well as the upwards direction of the melody in the first two beats. But a dynamic envelope like above gives a different, more melancholy feel, in which the stress is at the beginning of the phrase, then a sighing quality is maintained for the whole bar, the resolution only discovered in passing. Very loosely, I suppose I'd associate this with what very little I know about the inflections of some Slavic languages, though I believe Polish is the most Italianate sounding of them, with nodal points provided by relatively open vowel sounds? But that possible link may be entirely arbitrary. Anyhow, with the diminuendo, there seems to be a particular mode of melodic enunciation at play that is distinct from certain modes of taught inflection (whether horizontal or vertical, both would place the stress on the D-flat), which is extremely beautiful. Something I associate more with Russian players than Polish ones. Any thoughts? In particular, t-p? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Evan Johnson

|

|

« Reply #1 on: 14:45:47, 09-04-2007 » |

|

My copy is the Mikuli edition, which is basically entirely different dynamics-wise: crescendo through 33, descresc through 34, piano at 35 then crescendo through the bar; finally, decrescendi in the second half of the next three bars. I'm not sure I like the idea of that swell through the mini-"chorale" in 35-36; seems to me it should be more withdrawn throughout. Anyway.

I do love the 1-1-1-1-1 fingering in the right hand mm. 37-8; since that's in both Mikuli and Paderewski, can we assume that it's echt Chopin?

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #2 on: 17:12:33, 09-04-2007 » |

|

I do love the 1-1-1-1-1 fingering in the right hand mm. 37-8; since that's in both Mikuli and Paderewski, can we assume that it's echt Chopin?

No, it would be in italics in the Paderewski if it had been discovered in Chopin's hand. I'm not sure about the Mikuli edition; the one widely thought to be most authoritative is the Ekier. The difficulties with Chopin editions stem from the fact that his music was published simultaneously in Britain, France and Germany, often differing in each case! |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #3 on: 00:30:55, 10-04-2007 » |

|

Ok, my starter for ten: It's reasonably well-known now that Chopin, in the context of his time, strongly adhered to a principle (and a mode of teaching) whereby counterpoint is seen to precede harmony, the latter emerging as a by-product of the former. In this he was very much at odds with the new approaches of the time pioneered at the Paris Conservatoire, where the situation was reversed; Berlioz's music demonstrates this tendency (also to do with the fact that he was a guitarist rather than pianist, so more liable to think in terms of chords rather than lines). Anyhow, to me this not only accounts for the Bachian contrapuntal sophistication of Chopin's music (so often lost when played in an overly melody-dominated way), but also the vocal (rather than orchestral) quality of his piano writing. But a passage which always interests me is that below, from the Impromptu in G-flat Op. 51:  The edition used here is the Paderewski, which is now found very problematic; in the notes at the back it points out that the original editions have a crescendo at the beginning of bars 33 and 34, but all subsequent ones have the diminuendo. Which of these is employed significantly affects the musical sense: if a crescendo, then the dynamic envelope underlines the progression towards the A-flat minor near-resolution, as well as the upwards direction of the melody in the first two beats. But a dynamic envelope like above gives a different, more melancholy feel, in which the stress is at the beginning of the phrase, then a sighing quality is maintained for the whole bar, the resolution only discovered in passing. Very loosely, I suppose I'd associate this with what very little I know about the inflections of some Slavic languages, though I believe Polish is the most Italianate sounding of them, with nodal points provided by relatively open vowel sounds? But that possible link may be entirely arbitrary. Anyhow, with the diminuendo, there seems to be a particular mode of melodic enunciation at play that is distinct from certain modes of taught inflection (whether horizontal or vertical, both would place the stress on the D-flat), which is extremely beautiful. Something I associate more with Russian players than Polish ones. Any thoughts? In particular, t-p? You mean your "starter for Op. 10", do yo not?! "Counterpoint...seen to precede harmony"? I don't really buy into that in this context, although the contrapuntal urge is admittedly never far beneath the surface in some of Chopin's finest work. It's intersting that you invoke Berlioz, since that reminds me of a report I read of an interview with Boulez some years ago in which he spoke of the harmonic strengths of Chopin against the harmonic weakness of Berlioz, alongside the orchestral weakness of Chopin against the orchestral strengths of Berlioz. I'm not sure that I'm with him about Berlioz's harmonic weakness, but what struck me was Boulez's appreciation of Chopin's harmonic developments which, even in the early days, seem to me to be of very considerable sginificance and the full significance of which, even today, seems in some circles to be somewhat under-appreciated. That said, Chopin's best work is shot through with examples not unakin to the one you cite from what is perhaps the least often performed of his three Impromptus. Some of the sinuous movement in Op. 10 No. 5 is perhaps a rather different kind of example (how on earth did a mere teenager conceive and bring off those Op. 10 ╔tudes?!), the gorgeous Barcarolle has it in spades, there is the most remarkable contrapuntal passage towards the end of the B major nocturne, Op. 61 No. 1, there are similar instances in some of the mazurkas and this chromatic contrapuntal persuasion is in evidence as early as the Scherzo from the Piano Trio (see bars 13-16) which dates from even earlier than that first devastating set of ╔tudes. You write most appositely of "the Bachian contrapuntal sophistication of Chopin's music (so often lost when played in an overly melody-dominated way), but also the vocal (rather than orchestral) quality of his piano writing"'; these two things go very much hand in hand, it seems to me and, whilst I disagree with the way in which you express yourself in the use of the phrase "overly melody-dominated way" (of playing), I do know (I think!) where you are coming from here - you are, I believe, thinking of what I call the overly obsessive "right-hand-fifth-finger" approach to some of Chopin, of which even the late Shura Cherkassky could be guilty from time to time (I well recall his otherwise fascinating account of the four Ballades as the first half of a recital he gave some 20+ years ago in Cheltenham in which this persuasion tended to threaten to obscure certain important detail, despite how beautifully it was done). Returning to harmony in Chopin, of many so many fascinating examples I could cite, I am minded right now to think about that passage in the F minor Ballade in the section beginning in A flat major where, on the second quaver of bar 128, he implies an example of quartal harmony surely not to be seen again much before the opening measures of Sch÷nberg's Op. 9 First Chamber Symphony... Thanks for raising this topic - and now I'd better shut up about Chopin, otherwise no one else will get a word in edgeways!... Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 11:53:51, 10-04-2007 by ahinton »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #4 on: 00:42:07, 10-04-2007 » |

|

Very quickly - the stuff about counterpoint preceding harmony (in particular in the way it is taught, and the new approach pioneered by the Paris Conservatoire, which Chopin rejected) I get in large measure from Rosen (he talks about this at length in the context of both Chopin and Berlioz in The Romantic Generation); I've seen the subject invoked a few other places but haven't really checked primary sources in any detail (and I know some of Rosen's historical claims should be taken with a pinch of salt). I'm going to be away for a while and only sporadically at the computer; I'll do some looking up to find sources on this topic, and what Chopin said about it after I get back. Just the music itself and its approach to voice-leading gives me a very strong sense of the primacy of counterpoint, even in passages simply in chords (such as bars 35-36 of the above example, much my favourite of the Impromptus, also one of the few things I like Sofronitsky's playing of!). The fact that there was extensive timbral differentation between and within registers on the pianos Chopin favoured also served to aid contrapuntal clarity; I remember John Rink amply demonstrating this in a talk a few years ago, and have found so myself when playing some such instruments. The move towards timbral equality in modern pianos is as inappropriate for Chopin as the move towards evenness of tone from the fingers which he criticised.

|

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 00:43:49, 10-04-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #5 on: 10:05:46, 10-04-2007 » |

|

Very quickly - the stuff about counterpoint preceding harmony (in particular in the way it is taught, and the new approach pioneered by the Paris Conservatoire, which Chopin rejected) I get in large measure from Rosen (he talks about this at length in the context of both Chopin and Berlioz in The Romantic Generation); I've seen the subject invoked a few other places but haven't really checked primary sources in any detail (and I know some of Rosen's historical claims should be taken with a pinch of salt).

I half suspected as much. Now, whilst I would be most wary of questioning Rosen, what strikes me is how far towards maturity Chopin was even at the time of his earliest published works (rather as is the case with Medtner) and his harmonic grasp and contrapuntal felicities were accordingly both very much in evidence even before those ground-breaking Útudes of Op. 10. Just the music itself and its approach to voice-leading gives me a very strong sense of the primacy of counterpoint, even in passages simply in chords (such as bars 35-36 of the above example, much my favourite of the Impromptus, also one of the few things I like Sofronitsky's playing of!).

It gives me the very same - and there are many so many other instances of it in his work. The fact that there was extensive timbral differentation between and within registers on the pianos Chopin favoured also served to aid contrapuntal clarity; I remember John Rink amply demonstrating this in a talk a few years ago, and have found so myself when playing some such instruments. The move towards timbral equality in modern pianos is as inappropriate for Chopin as the move towards evenness of tone from the fingers which he criticised.

This is a real problem, for I also believe that Chopin's ╔tudes were not merely peaks in the history of pianism but also provided incentives to instrument designers to improve pianos to the point where that very kind of across-the-keyboard evenness was felt to be desirable in order to help the pianist bring the best out of music that, when it wants to, flings itself right across the entire range and sometimes demands similar subtleties of inflection and nuance at its extremes. I'm not arguing with what you write here, but I do think that, perversely, some of Chopin's work was in part (albeit also indirectly) responsible for the very developments that led to the kinds of piano that had become more the norm in the years immediately following the deaths of Liszt and Alkan. Would Chopin have regretted this aspect of his pioneering spirit and/or seen it as some kind of misappropriation of what he was about and what he wanted? who can say with certainty? Chopin was not alone in this, of course - Alkan's and Liszt's demands on player and instrument were likewise inevitably to lead in similar directions - but I rather think that Chopin, along with Beethoven in his final piano works, spearheaded this to some degree. Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #6 on: 11:08:59, 10-04-2007 » |

|

The fact that there was extensive timbral differentation between and within registers on the pianos Chopin favoured also served to aid contrapuntal clarity; I remember John Rink amply demonstrating this in a talk a few years ago, and have found so myself when playing some such instruments. The move towards timbral equality in modern pianos is as inappropriate for Chopin as the move towards evenness of tone from the fingers which he criticised.

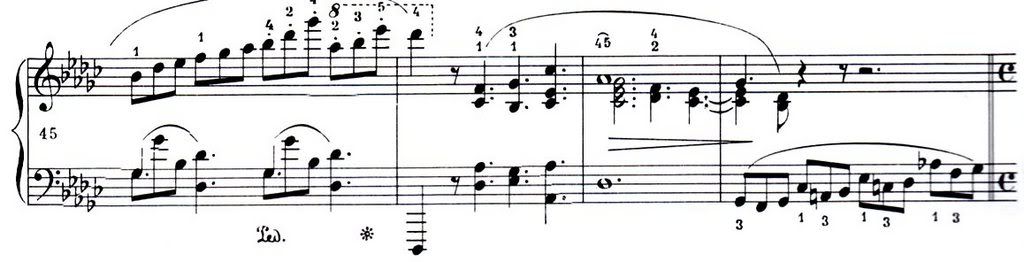

This is a real problem, for I also believe that Chopin's ╔tudes were not merely peaks in the history of pianism but also provided incentives to instrument designers to improve pianos to the point where that very kind of across-the-keyboard evenness was felt to be desirable in order to help the pianist bring the best out of music that, when it wants to, flings itself right across the entire range and sometimes demands similar subtleties of inflection and nuance at its extremes. I'm not arguing with what you write here, but I do think that, perversely, some of Chopin's work was in part (albeit also indirectly) responsible for the very developments that led to the kinds of piano that had become more the norm in the years immediately following the deaths of Liszt and Alkan. Would Chopin have regretted this aspect of his pioneering spirit and/or seen it as some kind of misappropriation of what he was about and what he wanted? who can say with certainty? Chopin was not alone in this, of course - Alkan's and Liszt's demands on player and instrument were likewise inevitably to lead in similar directions - but I rather think that Chopin, along with Beethoven in his final piano works, spearheaded this to some degree. No, I don't accept that, except possibly in Liszt's case (Liszt lent his advocacy to just about every piano that was placed in front of him, so it's very hard to gauge his preferences). In the process of developing pianos with deeper bass sonority and timbral equality throughout the registers, various intrinsic elements of both Chopin and Alkan's music wer ironed out. To stick with the G-flat Impromptu, the following passage:  has a thin silvery tone in the higher registers when played on a Pleyel or Broadwood piano of Chopin's time (less so on an Erard, though to an extent; bear in mind that Chopin's feelings on the Erard were more mixed), due to the particular physical characteristics, striking points, etc., which I defy anyone to emulate in quite the same way on a modern instrument. That is what makes it more than just simply a long arpeggio. Chopin favoured the weaker instruments of his time, not the stronger ones; that very fact makes me sceptical of the notion that his music, at least as he conceived it, implied future developments of the instrument. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #7 on: 11:52:22, 10-04-2007 » |

|

The fact that there was extensive timbral differentation between and within registers on the pianos Chopin favoured also served to aid contrapuntal clarity; I remember John Rink amply demonstrating this in a talk a few years ago, and have found so myself when playing some such instruments. The move towards timbral equality in modern pianos is as inappropriate for Chopin as the move towards evenness of tone from the fingers which he criticised.

This is a real problem, for I also believe that Chopin's ╔tudes were not merely peaks in the history of pianism but also provided incentives to instrument designers to improve pianos to the point where that very kind of across-the-keyboard evenness was felt to be desirable in order to help the pianist bring the best out of music that, when it wants to, flings itself right across the entire range and sometimes demands similar subtleties of inflection and nuance at its extremes. I'm not arguing with what you write here, but I do think that, perversely, some of Chopin's work was in part (albeit also indirectly) responsible for the very developments that led to the kinds of piano that had become more the norm in the years immediately following the deaths of Liszt and Alkan. Would Chopin have regretted this aspect of his pioneering spirit and/or seen it as some kind of misappropriation of what he was about and what he wanted? who can say with certainty? Chopin was not alone in this, of course - Alkan's and Liszt's demands on player and instrument were likewise inevitably to lead in similar directions - but I rather think that Chopin, along with Beethoven in his final piano works, spearheaded this to some degree. No, I don't accept that, except possibly in Liszt's case (Liszt lent his advocacy to just about every piano that was placed in front of him, so it's very hard to gauge his preferences). In the process of developing pianos with deeper bass sonority and timbral equality throughout the registers, various intrinsic elements of both Chopin and Alkan's music wer ironed out. To stick with the G-flat Impromptu, the following passage:  has a thin silvery tone in the higher registers when played on a Pleyel or Broadwood piano of Chopin's time (less so on an Erard, though to an extent; bear in mind that Chopin's feelings on the Erard were more mixed), due to the particular physical characteristics, striking points, etc., which I defy anyone to emulate in quite the same way on a modern instrument. That is what makes it more than just simply a long arpeggio. Chopin favoured the weaker instruments of his time, not the stronger ones; that very fact makes me sceptical of the notion that his music, at least as he conceived it, implied future developments of the instrument. Perhaps you're right after all - and, as a pianist (which I'm not), you ought to know better than I; it's just the way that certain aspects of some of Chopin's music struck me. You are right, of course, that Chopin generally prized Pleyels over ╔rards, but I cannot help but remain fascinated (and that's all I'll ever be able to be, of course!) by the prospect of observing Chopin's reactions to, say, the Steinways of the 1890s, the Mason & Hamlins of the 1920s and 1930s and the best of modern B÷sendorfers in the context that many pianists were still determined to play Chopin's music on them (of these, B÷sendorfer was the only manufacturer that made instruments in Chopin's own lifetime, although Chopin would almost certainly not have known them, as the firm was still very much in its infancy at the time Chopin died). If indeed we are left with a problem here, I think that it may be one of perceptual conflict between, on the one hand, whether Chopin, for all his vision, could not necessarily envisage the future of piano design and manufacture and its significance for the future of his own music (including whether his development of piano writing would have had an indirect part to play therein) and, on the other hand, whether our current view of Chopin's music and its performance might have become unduly coloured by our long-standing familiarity with pianos that he never lived to encounter... Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Evan Johnson

|

|

« Reply #8 on: 14:00:04, 10-04-2007 » |

|

Chopin favoured the weaker instruments of his time, not the stronger ones; that very fact makes me sceptical of the notion that his music, at least as he conceived it, implied future developments of the instrument.

On that note, Ian, do you know of any particularly recommendable Chopin recordings on period pianos? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

richard barrett

Guest

|

|

« Reply #9 on: 14:30:04, 10-04-2007 » |

|

I'm quite fond of a compilation of (all too) familiar pieces played by Janusz Olejniczak on the Opus 111 label, and also Patrick Cohen's complete Mazurkas on Glossa, actually now I look at the shelves that's all the Chopin I have on CD, and, given my not-very-high level of interest in and knowledge of this music I dare say these choices will be found by the experts to be sadly wanting in taste. Still, there it is.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

trained-pianist

|

|

« Reply #10 on: 16:47:56, 10-04-2007 » |

|

This particular section in op 51 Impromtu is difficult because there are so many repetitions of the same idea. The fact that earlier editions had different dynimic marks and Mikuli ed (we know thanks to Evan Johnson) are different telles that there are many ways to play this particular section and Chopin would agree. One can sometimes play with cresc and make the intonation more positive and sometimes less. Sometimes everything can come out of the first long note and some times not. Thank you for this discussion Ian, It is very interesting. For a while I thought Chopin was dismissed as a whining sick composer and his striking harmonies were dismissed. He was also thought as sentimental salon composer. I am glad many people here appreciate him. I have a student playing Db major nocturne at the moment and we go through such a beautiful harmonies together. This is a winner of Chopin competition. Did anyone hear him? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rageOzbaWz4I am going to read through this thread and may be write something else. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

trained-pianist

|

|

« Reply #11 on: 19:51:19, 10-04-2007 » |

|

Every language has different melodic ways of speaking. Ian was talking about particular intonation in Chopin Impromtu op. 51.

In Polish and Russian intonation is very important because the order of words in question and statement is the same. The difference is only intonation. They rely a lot on intonation for expression of many things. One can do it in English to (by emphisising different words in a sentence the meaning is changed). That goes for the particular section in question. I am just making it clearer (I think) that everything can be played in many different ways).

I think Polish and Russians have a way with rubato which is a key thing for Chopin.

It is interesting to talk about rubato. Who wrote that he was listening to Chopin teaching a piece in 3/4 time and conducted it in 4/4. And they had an artument with Chopin.

Freedom is all important in playing Chopin.

Different composers have different rubato. Schumann's rubato was for specific place (short ) expressed in rit sign.

I think it is his German way of thinking (more structured and less free). Sometimes I am listening to pianists playing Schumann and thinking that they have wrong rubato.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #12 on: 23:14:14, 10-04-2007 » |

|

Every language has different melodic ways of speaking. Ian was talking about particular intonation in Chopin Impromtu op. 51.

In Polish and Russian intonation is very important because the order of words in question and statement is the same. The difference is only intonation. They rely a lot on intonation for expression of many things. One can do it in English to (by emphisising different words in a sentence the meaning is changed). That goes for the particular section in question. I am just making it clearer (I think) that everything can be played in many different ways).

I think Polish and Russians have a way with rubato which is a key thing for Chopin.

It is interesting to talk about rubato. Who wrote that he was listening to Chopin teaching a piece in 3/4 time and conducted it in 4/4. And they had an artument with Chopin.

Freedom is all important in playing Chopin.

Different composers have different rubato. Schumann's rubato was for specific place (short ) expressed in rit sign.

I think it is his German way of thinking (more structured and less free). Sometimes I am listening to pianists playing Schumann and thinking that they have wrong rubato.

Do you think, t-p, that Russian and Polish performers, if just playing in a way that seems 'natural', without thinking more about it, would play that phrase in a different manner, and would that relate to characteristic phrase contours in the different languages? I'm imagining (almost for sure this is a woeful simplication) that the Russians would be more likely to put the stress at the beginning and die away from that, whereas the Poles would find various high points within the phrase (as would Italians, corresponding to open vowel sounds if it were a vocal melody)? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #13 on: 23:30:09, 10-04-2007 » |

|

Returning to harmony in Chopin, of many so many fascinating examples I could cite, I am minded right now to think about that passage in the F minor Ballade in the section beginning in A flat major where, on the second quaver of bar 128, he implies an example of quartal harmony surely not to be seen again much before the opening measures of Sch÷nberg's Op. 9 First Chamber Symphony...

Not having my scanner with me where I am (out of the country), and so unable to copy the passage in question and post it here, I would direct people to http://www.imslp.org/wiki/Ballade_No.4_%28Chopin%2C_Frederic%29 to see the passage Alistair is referring to. Open the PDF file, go to page 6, look at the first bar of the fourth system. Incredible stuff. (for those looking at this thread, do also look at the Scriabin thread in the 20th century sub-board of the Music Appreciation section - various stuff about Chopin is included there) |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #14 on: 23:36:28, 10-04-2007 » |

|

Chopin favoured the weaker instruments of his time, not the stronger ones; that very fact makes me sceptical of the notion that his music, at least as he conceived it, implied future developments of the instrument.

On that note, Ian, do you know of any particularly recommendable Chopin recordings on period pianos? The Olejniczak recording that Richard mentions is well worth having, also do check out the Emmanuel Ax/Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment recordings of the concertos (though in those cases I find the orchestral playing more interesting than that on the piano). I have a couple of recordings of the Nocturnes and Waltzes on period instruments at home, but can't remember the names of the pianists offhand (one of those recordings is very good, others less so), which I will post details of when I get home. There is a big set on Brilliant Classics (very cheap) of Chopin, much on period instruments, which I don't have, but have heard very good things about, worth checking out. Also do try the Zimmerman recordings mentioned elsewhere; not period instruments but an acute sense of period style. Richard - do check out the Second and Fourth Ballades, the Polonaise Fantasy, the Second Piano Sonata (in terms of your own tastes, especially the last movement) and the later Mazurkas, if you don't already know them. I think you might find some of those remarkable. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|