|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #30 on: 16:11:08, 17-04-2007 » |

|

for it's a bit ridiculous in concert just to watch people clicking on their mice and fortunately one doesn't see too much of that kind of thing any more. Presumably because you've exported it all to us... no end of concerts performed up on the Mac Laptop here, I'm afraid. I remember one in Sydney a while back which was reviewed as 'about exciting as watching people knit'. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

roslynmuse

|

|

« Reply #31 on: 16:17:00, 17-04-2007 » |

|

There are ways to make anything exciting... |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Evan Johnson

|

|

« Reply #32 on: 17:18:19, 17-04-2007 » |

|

The famous case of the four Cs in Superscriptio springs to mind: there are two dotted demisemiquavers in a 3/48 bar, then two straight demisemiquavers in a 'normal' bar. (I forget what it is - I don't have it in front of me.) In other words, two dotted demis under a triplet followed by two straight demis; in other other words four equally spaced notes, and they're all staccato. Felix Renggli does indeed manage to phrase them so that the second note sounds as an offbeat and in my opinion that's absolutely right - but it's an expressive and a formal decision as well as a purely mathematical one.

Although it's a little more complicated than that, because (as I have just discovered from the tattered xerox on my shelf) the 3/48 bar (it's on the first system of p. 6) is preceded by two 3/24 bars, and thus the "triplet" pulse has had, in theory anyway, some time to establish itself. Of course, the first of the 3/24 bars consists of a dotted sixteenth (sorry, semiquaver...) followed by a dotted sixteenth (sorry, semiquaver...) rest. Oh dear. The point is simple though: that second dotted note in the 3/48 bar is "syncopated," or in fact merely syncopated without quotes. One ought to do a composer the courtesy of assuming that his or her notations mean something, after all. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Evan Johnson

|

|

« Reply #33 on: 17:37:52, 17-04-2007 » |

|

[...]

I would think you'd agree that executing a series of straight 1/8 notes (the opening of the Waldstein Sonata, say) is less mentally or motorically demanding than a series of nested tuplets of constantly varying durations and speeds,

I'm not sure I would agree; I guess it depends on what you mean by "mentally demanding." As OS mentioned, I imagine (being only a thoroughly mediocre pianist myself who couldn't possibly play the Waldstein with anything resembling musical control) that the slow gradations of intensity and the requirement that, in this case at least, absolute regularity is musically necessary are quite demanding indeed, mentally and muscularly. It's different, of course, and sort of pointless to compare; the Ferneyhovian (or whoever-ian) difficulties are along a different axis than the Beethovenian ones, and require different mental musculature, which is the main reason they are "difficult." For performers who are used to that sort of notational rhetoric, I imagine the main difference is the addition of one relatively trivial if perhaps time-consuming step: figuring out how it fits together. The point is not simply that BF's notation spells out many of the things a traditional score tacitly assumes, but also that the MUSIC makes cognitive demands that Beethoven does not. [...] All the talk of notation re Ferneyhough is a bit of a red herring, in my opinion, as it easily overlooks the fact that the MUSIC is actually hard to play, that it's not simply a matter of complex notation. I'm sure Evan will agree that it's a form of meta-negational circumscription.  Well hello, quartertone, you have outed yourself... in a fairly limited fashion, of course. anyway, I don't think I agree with the above either. I don't find BF's work (at least after about 1980) to be much more musically demanding than, say, Berg. The expression seems fairly straightforward, the gestures are clearly defined and functional; there is very little there (again, after and including, let's say, Chute d'Icare) that contradicts an intuitive understanding of musical functioning. For me, Ferneyhough's music is just as much music on the page as most other, more straightforwardly presented work; the link between the score and a "musical experience" seems to be much closer in Ferneyhough to Beethoven than it is to, say, the famous Cassidy. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

quartertone

|

|

« Reply #34 on: 20:12:30, 17-04-2007 » |

|

Personally I'd sooner suggest that performing a C natural on a violin in many contexts, for example in unison with a piano, requires very considerably closer than 1/8 tone accuracy... In that context, sure. In a context like a string quartet, however, e.g. where the C is the leading note in D flat major, I believe the sharpness of the C would be calibrated more intuitively. also that in a passage such as the opening of the Waldstein, maintaining a constant balance over the sequence of chords while shaping the overall dynamic is damn hard work, more so than in a 'Ferneyhovian' context in that in such transparent music the slightest deviation from regularity is immediately perceived. Well, the noticeable nature of inaccuracy is ultimately a major factor in this entire debate; very few listeners will notice whether you switched around pages 8 and 9 of Time and Motion I in a concert, let alone whether the figure in bar x was articulated correctly. That would make most New Music "easier" than traditional music, as there's little or no corrective; but obviously I'm not accepting faking it as a valid mode of performance. But with the parametric detail in "complex" music such things as the Waldstein build-up can be multiplied, e.g. the sort of thing you get in Richard's Tract, where the pianist has 3-4 voices following different dynamic curves, and each is supposed to be smooth. I would certainly also argue strongly (and from a certain amount of experience) against the notion that "the performer of BF's music will probably often be too tied-up mentally to consider the different expressive possibilities of a passage". I'd say that your experience is actually a significant factor here; you've been playing such music longer than most, so some of the challenges that differ so greatly from more traditional music are familiar to you. My music uses some similar parametric configurations, and I've worked both with performers experienced and inexperienced in these things, so I can compare the experience. The less experienced performers, if they are sufficiently open to take the plunge, tend to feel slightly out of their depth, but often experience an exhilarating sort of self-transcendence as a result of being pushed to places they hadn't conceived of. But such performers, in my experience, are certainy fairly tied-up mentally, and will need a lot of pointers from me as to "expressive" matters, if they're even free to act on them. Also, the discussion of notation so far seems to have tacitly assumed a solo context, but with the sort of rhythmic complexity we're dealing with here, coordination and balance in ensemble music are a whole other can of worms. Engagement with (not only) Ferneyhough's music involves you (well, it involves me) with expressive choices from the outset - for example, the answer to 'how loud is ff' depends on what the ff is there for and expression can't be factored out of that consideration Sure, I wasn't actually stating otherwise. But for the novice, the priorities tend to be more pragmatic, and the expressive functions of different physical parameters might not yet be understood. Or, for example, the notion that a crescendo on a particularly "weak" microtonal fingering is intended to highlight its sonic instability, as a way of reflecting the instrument's unique constitution, rather than simply being a result of the composer's ignorance. These realisations are going to take some time and analysis if the composer isn't at hand to point them out directly. Felix Renggli does indeed manage to phrase them so that the second note sounds as an offbeat and in my opinion that's absolutely right - but it's an expressive and a formal decision as well as a purely mathematical one. Of course, though I do wonder whether you'd hear that without having seen the score (not that that would invalidate it). |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #35 on: 20:45:14, 17-04-2007 » |

|

very few listeners will notice whether you switched around pages 8 and 9 of Time and Motion I in a concert, let alone whether the figure in bar x was articulated correctly. That would make most New Music "easier" than traditional music, as there's little or no corrective; but obviously I'm not accepting faking it as a valid mode of performance. Ah, I rather think they would notice. T&M I only has 8 pages.  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

quartertone

|

|

« Reply #36 on: 21:02:33, 17-04-2007 » |

|

Ah, I rather think they would notice. T&M I only has 8 pages.  Ha, I knew you'd say that! But I'm sure you could improvise a convincing page 9 for those not in the know... |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

quartertone

|

|

« Reply #37 on: 07:02:04, 18-04-2007 » |

|

I'm not sure I would agree; I guess it depends on what you mean by "mentally demanding." As OS mentioned, I imagine (being only a thoroughly mediocre pianist myself who couldn't possibly play the Waldstein with anything resembling musical control) that the slow gradations of intensity and the requirement that, in this case at least, absolute regularity is musically necessary are quite demanding indeed, mentally and muscularly. Well, then try doing that at four different speeds in four different voices: one going at 10:7, one at 7:6, one and 11:8 and one at 11:9. Not harder at all, eh? And how about in an ensemble? Try getting 8 players to play an uninterrupted sequence of 11:11, 11:10, 11:9, 11:8 in unison (without a conductor to beat the irrationals as tempi) and tell me it's no harder than straight 1/8 notes. Well hello, quartertone, you have outed yourself... in a fairly limited fashion, of course. Yes, very limited. You mean you didn't guess from the Hübler avatar?  anyway, I don't think I agree with the above either. I don't find BF's work (at least after about 1980) to be much more musically demanding than, say, Berg. Ever played it? The expression seems fairly straightforward, the gestures are clearly defined and functional; there is very little there (again, after and including, let's say, Chute d'Icare) that contradicts an intuitive understanding of musical functioning. Those are the words of someone who's been familiar with his music for a while; consider how it is when these phenomena are new to a listener or performer. For me, Ferneyhough's music is just as much music on the page as most other, more straightforwardly presented work; the link between the score and a "musical experience" seems to be much closer in Ferneyhough to Beethoven than it is to, say, the famous Cassidy. Well, there's no pretence of "deconstruction", but I don't think that's of much consequence in this case. As for "famous"... |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 07:04:45, 18-04-2007 by quartertone »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #38 on: 07:45:47, 18-04-2007 » |

|

Not harder at all, eh? And how about in an ensemble? Try getting 8 players to play an uninterrupted sequence of 11:11, 11:10, 11:9, 11:8 in unison (without a conductor to beat the irrationals as tempi) and tell me it's no harder than straight 1/8 notes. Well, there at least is a concrete example, but isn't it a rather artificial one? In any case I would indeed say that on pianos or other instruments with sharp attack the example you've listed is indeed not a great deal harder than straight quavers, depending of course on the tempo. I think you're overlooking the fact that deviation from the kind of regularity transparent to any listener is perceptible in a way that deviation from the exact notation of a complex demand is not. I maintain that that's a musical reality. Talking about 'difficulty' in the abstract is rather, well, difficult when perception plays such a part and in music there's no way out of that. Musically speaking if a task can be done perfectly then it has to be - it's not that listeners suddenly become less forgiving people when listening to Mozart, just that they generally know all the notes and that a deviation from them automatically will be distracting to the listener's perception in a way that already, for example, a smudged note in a passage of Liszt double octaves won't be, let alone whether my 19:16 was really closer to 19:15 1/2. It's a two-way street. And yes, I have played (and conducted) Berg and I have played (and conducted) recent Ferneyhough, and I wouldn't say the latter is more musically demanding. Apart perhaps from the need to use a calculator to find where the beat is relative to the notes because the performing materials for Brian's music aren't proportionally notated, but I don't see that demand as inherently musical.  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

quartertone

|

|

« Reply #39 on: 08:07:37, 18-04-2007 » |

|

Well, there at least is a concrete example, but isn't it a rather artificial one? No more artificial than any of these irrationals; there are some bits in my pieces that aren't a million miles away. In any case I would indeed say that on pianos or other instruments with sharp attack the example you've listed is indeed not a great deal harder than straight quavers, depending of course on the tempo. I'm not so sure Ian would agree with you. I hope he gets un-suspended soon so that he can comment himself (he has referred to Tract as one of the hardest piano pieces ever, so...) I think you're overlooking the fact that deviation from the kind of regularity transparent to any listener is perceptible in a way that deviation from the exact notation of a complex demand is not. On the contrary; if you take another look at my previous posts, you'll see that I've by no means overlooked it. But I thought we were talking about accurate execution, not whether the accuracy is detected by listeners or not? If the latter were the standard, most New Music could simply be bluffed through. Some do that, of course... Musically speaking if a task can be done perfectly then it has to be - it's not that listeners suddenly become less forgiving people when listening to Mozart, just that they generally know all the notes Or even if they don't, the stability of the musical language can give pretty strong hints as to what might be wrong notes. I think you're assuming rather a lot if you think "they generally know all the notes"! (I certainly don't!) and that a deviation from them automatically will be distracting to the listener's perception in a way that already, for example, a smudged note in a passage of Liszt double octaves won't be, let alone whether my 19:16 was really closer to 19:15 1/2. Well yes, but again, aren't we talking about the difficulty of accurate execution, not the listener's ability to perceive the difference? And yes, I have played (and conducted) Berg and I have played (and conducted) recent Ferneyhough Well, I know you have, and have been familiar with the challenges we're talking about for something like 15 years (?), but you're hardly representative. Playing irrationals or microtones is pretty old hat for you. Apart perhaps from the need to use a calculator to find where the beat is relative to the notes because the performing materials for Brian's music aren't proportionally notated Neither are his scores; it makes me wonder about the precision of his musical imagination regarding the relationships between different instruments, I must say. I can't imagine even composing this stuff without using proportional notation, which I've done for a while now. but I don't see that demand as inherently musical.  That's not the point; I referred to mental and motoric challenges. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #40 on: 14:35:32, 18-04-2007 » |

|

Hm. Sort of my point really - mental and motoric challenges separated from music aren't particularly interesting to me in themselves. At some level of measurement you'd be hard put to find two notes anywhere, played by anyone, in any repertoire, that were exactly the same length or dynamic. But sometimes they're exactly the same on the page. So what does 'inaccurate' mean? Back to perceptions. I don't think you can divorce the two. Not without implying a degree of rigidity to musical notation that I suspect no composer or musician has ever expected or been capable of (or interested in!). Is rubato 'inaccuracy'? What about emphasising downbeats in many areas of the repertoire? Perhaps one can say that in certain repertoire it's encoded into the notation by convention. But then how much is 'inaccurate'? And so on. Isn't the construction of a viable framework for engaging with the notation, which will almost always involve deviation from the exact temporal proportions it presents, a huge part of what musicality is all about? but you're hardly representative Oh, right, well, not much point my saying anything then.  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

quartertone

|

|

« Reply #41 on: 14:54:29, 18-04-2007 » |

|

Hm. Sort of my point really - mental and motoric challenges separated from music aren't particularly interesting to me in themselves. I never said they were interesting, just that they came into the equation. At some level of measurement you'd be hard put to find two notes anywhere, played by anyone, in any repertoire, that were exactly the same length or dynamic. Well obviously, we're not machines. Is rubato 'inaccuracy'? Not musically speaking, though one can certainly be too liberal with it. But the rubato is applied to a clear notion of what the "fixed" rhythm would be. Even if that notion is abstract, it still has to exist before you can carry out a rubato, otherwise you wouldn't know what you were doing. And so on. Isn't the construction of a viable framework for engaging with the notation, which will almost always involve deviation from the exact temporal proportions it presents, a huge part of what musicality is all about? Of course. But you must acknowledge that Brian's notation, or that of many other composers, specifies a lot of parameters that other composers would either transmit orally to performers or leave entirely to them, and are hence absent from the written score. Pretty much every note I write has an articulation mark on it, but plenty of composers don't do that, so they will leave more space for (mis)interpretation than I do. If one is composing and notating so many parameters - tiny dynamic fluctuations, timbral specifications, very subtle rhythmic inflections, articulations - you can't tell me that isn't making more fixed demands of the musician(s) than a score (or piece) with none of those details. Because it's ruling out a number of liberties the player might otherwise take. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Reiner Torheit

|

|

« Reply #42 on: 16:37:54, 18-04-2007 » |

|

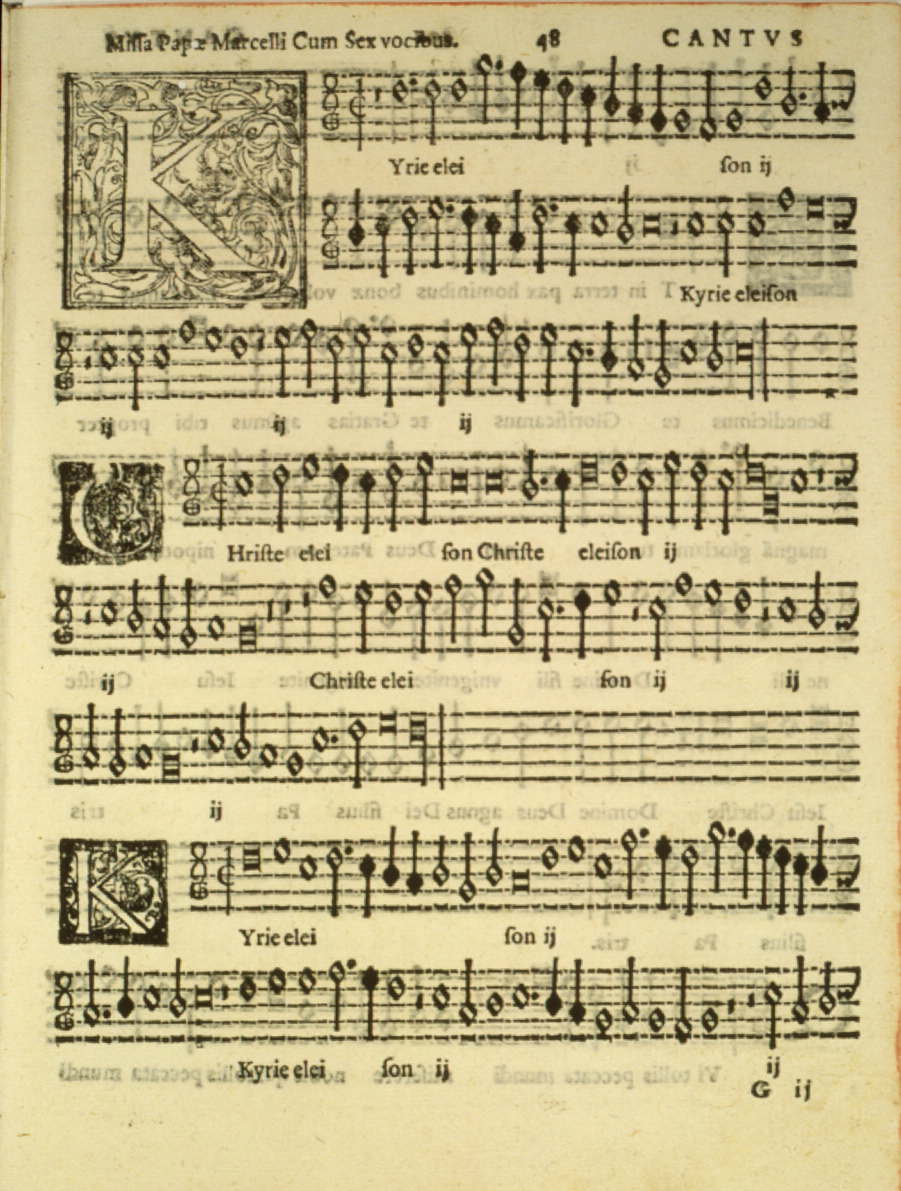

What about emphasising downbeats in many areas of the repertoire? And conversely, prior to 1600 there are no barlines at all in most music - how should that be interpreted? I am not trying to hijack this thread in the direction of HIP, but any discussion of the "meaning" of barlines must also cover their absence... are they just a visual aid to numeric note-groupings, or do they imply interpretative elements such as "downbeats". We ought to remember that in principle barlines are convenient, but play no role at all and could in theory be omitted from printed music... as they once were.  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

"I was, for several months, mutely in love with a coloratura soprano, who seemed to me to have wafted straight from Paradise to the stage of the Odessa Opera-House"

- Leon Trotsky, "My Life"

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #43 on: 16:45:15, 18-04-2007 » |

|

If one is composing and notating so many parameters - tiny dynamic fluctuations, timbral specifications, very subtle rhythmic inflections, articulations - you can't tell me that isn't making more fixed demands of the musician(s) than a score (or piece) with none of those details. Because it's ruling out a number of liberties the player might otherwise take. In fact simply because the composer makes more demands doesn't necessarily make the music more demanding. At least not for this unrepresentative musician. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Evan Johnson

|

|

« Reply #44 on: 16:58:27, 18-04-2007 » |

|

I don't have time right now to get into this too fully, but I wanted to leave one thought: Of course. But you must acknowledge that Brian's notation, or that of many other composers, specifies a lot of parameters that other composers would either transmit orally to performers or leave entirely to them, and are hence absent from the written score. Pretty much every note I write has an articulation mark on it, but plenty of composers don't do that, so they will leave more space for (mis)interpretation than I do. If one is composing and notating so many parameters - tiny dynamic fluctuations, timbral specifications, very subtle rhythmic inflections, articulations - you can't tell me that isn't making more fixed demands of the musician(s) than a score (or piece) with none of those details. Because it's ruling out a number of liberties the player might otherwise take.

Consider this: I would posit that in any relatively "modern" music (modern meaning post-1800, say), there is a certain amount of mental and motor activity, and fineness of that activity, that goes into performance. I don't think that amount varies as much from one composer to another, or one century to another, or whatever, as it may seem. The question of how much is specified in the score adds another layer to the process of learning, of course, but it is a relatively trivial one, musically speaking (which is not to say that the results are trivial!). When BF adds expressive markings and rhythmic nuances and dynamics and articulations to a passage that other composers, or older composers, would be content to leave with a slur and a crescendo, I am still not convinced that he makes the act of performance any more difficult. He makes the act of reading the score more difficult, and the act of internalizing the various indications more difficult for the trivial reason that there are more of them; but when it comes time to apply finger to keyboard or fingerboard or trill key, I think the amount of effort is more or less the same. Another way of putting it: the "difficulty" of Ferneyhough's music (too bad for him, incidentally, that he has become enough of an ex post facto figurehead to always be the go-to proper name in conversations like this!) is, as has become pretty well understood, the result of an attempt to encode a performance practice within a particular work that is sufficiently subtle and flexible, mutatis mutandis, to "compete" affectively with that that is implicit in earlier music. The problem, then, is a matter of learning; of performers' musical education. Which is not to say that it isn't real; but it is to say that it isn't inherent. The fact that Herr Sudden or Ian have, after years and years of performance of this repertoire, internalized its difficulties, seems to me to show quite conclusively that those difficulties are fundamentally illusory. You say that OS is not a typical case; that is true; but, after all, the technical challenges of Mozart's piano sonatas are terminally daunting to beginning players. It's just that the category of "beginning players" when it comes to Ferneyhough is much, much larger, and much more professionally accomplished on average! |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|