|

trained-pianist

|

|

« Reply #45 on: 10:34:03, 20-04-2007 » |

|

Reiner, I am with you on this one. The more they invent the more they know it had been tried already.

The old music did not use bar lines too. And the old instrument was fantastic on the other thread.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #46 on: 11:40:12, 20-04-2007 » |

|

Not harder at all, eh? And how about in an ensemble? Try getting 8 players to play an uninterrupted sequence of 11:11, 11:10, 11:9, 11:8 in unison (without a conductor to beat the irrationals as tempi) and tell me it's no harder than straight 1/8 notes. Well, there at least is a concrete example, but isn't it a rather artificial one? Well, near the beginning of Ferneyhough's Second String Quartet, after the opening violin solo, the second violin plays several bars in rhythmic unison with the first, involving two level nested tuplet groups throughout (as well as extremely detailed dynamics, articulation, and so on). I reckon that's a lot harder to get together than would be the case with more simple metrical units. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #47 on: 13:08:13, 20-04-2007 » |

|

Oddly enough you've chosen the very example that Roger Marsh took a potshot at in the Musical Times a while back in a rather ridiculous article. He wrote down what the music as played by the Ardittis sounded like to him (a jolly 6/8, I seem to remember) and then compared that with the durational proportions of the score, giving % inaccuracy values on that basis. Not on the basis of having calculated the actual durations in performance, dearie me no.

Back to the old perception thing.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

quartertone

|

|

« Reply #48 on: 13:11:15, 20-04-2007 » |

|

But Ollie...that's not an answer to the question. What do you think of that example (it should have occurred to me too, and I'm sure there are similar ones)?

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #49 on: 13:19:05, 20-04-2007 » |

|

I saw no question, and if there had been I think you'll find the answer to it among my previous posts. But anyway. Musically speaking if a task can be done perfectly then it has to be - it's not that listeners suddenly become less forgiving people when listening to Mozart, just that they generally know all the notes and that a deviation from them automatically will be distracting to the listener's perception in a way that already, for example, a smudged note in a passage of Liszt double octaves won't be, let alone whether my 19:16 was really closer to 19:15 1/2. It's a two-way street. What do you actually mean by 'difficult'? I suspect we're going to continue to talk at cross-purposes for a while until we sort that out. (What do I mean by difficult? Difficult to realise in performance to my own satisfaction (relative to my own abilities and to my perception of the notation's parameters), and to the satisfaction of my imagined ideal listener. That might be a starting point.) |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #50 on: 14:00:41, 20-04-2007 » |

|

It's different, of course, and sort of pointless to compare; the Ferneyhovian (or whoever-ian) difficulties are along a different axis than the Beethovenian ones, and require different mental musculature, which is the main reason they are "difficult." For performers who are used to that sort of notational rhetoric, I imagine the main difference is the addition of one relatively trivial if perhaps time-consuming step: figuring out how it fits together. There are many other issues to address when playing music with a highly individuated approach to notation, such as Ferneyhough's. In particular, not just ' what does the notation tell us' but also ' why has he notated it this way' (which may vary from piece to piece, or at least between different sub-sections of his output). That can affect one's whole approach to performing the rhythms, and so on. The very first bar of Opus Contra Naturam includes four levels of nested irrational rhythms; also there is a different tempo marking for almost every bar afterwards (things like quaver/eighth-note=71.3, and so on). Devising strategies in order to somehow make sense of this notation is indeed a difficult process. Other parameters are also notated with a high degree of detail. Now, if there was less detail and more reliance on the performer's own choices in some of these respects, the difficulties would be of a different nature, to do with personal approaches to how one stresses certain notes, shapes lines, uses rubato, and so on. But in the case of Ferneyhough, it's not simply a case of all these things being already 'answered' by the score; in other cases there will be a degree of reliance upon shared common practices which can be executed intuitively (Beethoven was a pioneer of new performing practices and approaches to notation, but there is still a fair degree of commonality between those he expected and those which preceded him), whereas Ferneyhough's notation is radically counter-intuitive, aiming to channel performers' creative imagination away from such things. In the process of so doing, his music and musical notation focusses attention more acutely on the precise meaning of all sorts of basic symbols to do with rhythm, dynamics, etc., which occupy a more foregrounded position. These need personalised interpretation every bit as much as in any music. In summary, I do think the rhythmic difficulties of Ferneyhough are of a different order, and would be surprised if many who either approach Beethoven Waldstein for the first time, or Ferneyhough for the first time, would really disagree? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #51 on: 14:34:02, 20-04-2007 » |

|

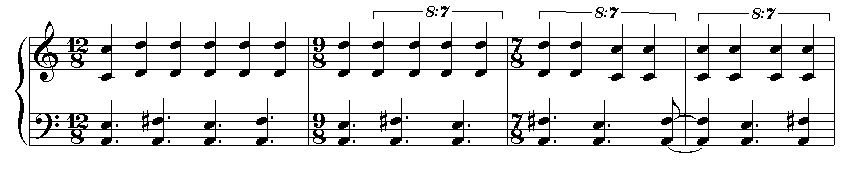

In any case I would indeed say that on pianos or other instruments with sharp attack the example you've listed is indeed not a great deal harder than straight quavers, depending of course on the tempo. I'm not so sure Ian would agree with you. I hope he gets un-suspended soon so that he can comment himself (he has referred to Tract as one of the hardest piano pieces ever, so...) is a very particular and very complex (sorry for that word!) example. The sort of thing that quartertone's original example entailed makes me think of a passage in Christopher Fox's lliK-relliK, where you have some octaves in the right hand in crotchets played against alternating chords in dotted crotchets in the left. Then he shifts the rhythm in the right hand to be in a ratio of 8:7 quavers for groups of four crotchets, whilst the left hand remains steady. That entails gauging the correct relationship so that the right hand groups can remain even, be fitted into the appropriate period of time, so as to form the appropriate new metrical relationship with the left. Then a few bars later, the right hand shifts into dotted quavers. Here is the passage in question  Now, I don't find this that difficult, perhaps because I'm used to playing all sorts of complex (whoops, done it again!  ) rhythms, but it's without doubt trickier than simply playing straight crotchets. To Reiner's point: I am not trying to hijack this thread in the direction of HIP, but any discussion of the "meaning" of barlines must also cover their absence... are they just a visual aid to numeric note-groupings, or do they imply interpretative elements such as "downbeats". We ought to remember that in principle barlines are convenient, but play no role at all and could in theory be omitted from printed music... as they once were. Certainly, and this becomes an issue in quite a bit of contemporary music - do the barlines, or for that matter the beaming, imply certain stresses and counter-stresses (I was giving a lecture on this very subject last week)? Composers use different practices (sometimes misleading) in this respect. Xenakis, in the notes to his piano piece Herma, makes clear that they are purely there for notational convenience - however, considering the performer reads them, and guages the rhythms relative to a beat, I wonder how possible it is to entirely avoid one's way of thinking the music being reflected in the performance? There is no really 'neutral' way of notating a-metrical, unbarred music. In the case of early vocal music, presumably such other factors as the nature of the melodic shapes, contrapuntal correspondences, or the stresses implied by the text, can play a part in answering questions about implied pulse grouping where there are no barlines. |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 14:46:48, 20-04-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #52 on: 12:03:47, 23-04-2007 » |

|

Whilst what Ian has to say here is all very true, it is inevitably informed from the experienced performer's perspective, whereas I think that there is also from time to time the additional problem for the listener that, even when the performer has mastered such rhythmic intricacies as well is as humanly possible, there remains the question as to the extent to which even the most aurally adept listener may be expected consistently to attune him/herself accurately to the precise nature of those intricacies, especially when listening to a performance without a score? Whilst there can be no possible "correct" answer in respect of this issue (especially given its inherent "where do you draw the line?" implications), I cannot help but suspect that a law of dimishing returns may well have some relevance here in certain cases.

Best,

Alistair

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

George Garnett

|

|

« Reply #53 on: 13:03:41, 23-04-2007 » |

|

I have to say that thought was lurking in my mind too when reading this thread but, given all the effort that composers and performers put into getting these things right, it seemed a bit impolite to mention it. The argument in the other direction, I suppose, is that we hapless listeners do manage to take notice (though how I'm not at all sure) of the tiniest and most fleeting micro-changes in rhythm in jazz and improvised music and indeed in the performance, as opposed to the writing, of music generally. We couldn't possibly notate all of these things but they are still picked up somehow by the listener as expressively important. I suppose one question, therefore, is whether this sort of 'subconscious' precision and/or complexity (which kind of go together) can usefully be written into the music in advance by the composer sitting at a desk or whether it can only be done 'on the fly' in performance if it is to have expressive significance. And another question might go: OK, so we know that some of these very subtle features can indeed somehow be picked up by listeners but the cases we know of tend to be localised features to do with 'phrasing' and 'expression'. Does this particular ability (which it is juicily tempting to come up with an evolutionary explanation for) really extend to the sort of complex (sorry), micro-managed (even sorrier) sort of writing that is being discussed here and which, I take it, is as much to do with larger scale structure as it is to do with the immediacy of local expressiveness. (Hmm, dubious dichotomy there perhaps, not to mention a suspiciously loaded sounding question, but having got this far...  ). |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 13:08:30, 23-04-2007 by George Garnett »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #54 on: 13:37:58, 23-04-2007 » |

|

If I may venture to suggest that listeners are unlikely to pick up quite a number of the details (in the sense they could discern how they are notated, certainly in a rhythmic sense), but if the performer were to get them wrong (at least to any substantial degree) they would hear the difference, without necessarily knowing exactly why. All of these details are means to ends rather than necessarily ends in themselves.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Evan Johnson

|

|

« Reply #55 on: 13:49:08, 23-04-2007 » |

|

whereas I think that there is also from time to time the additional problem for the listener that, even when the performer has mastered such rhythmic intricacies as well is as humanly possible, there remains the question as to the extent to which even the most aurally adept listener may be expected consistently to attune him/herself accurately to the precise nature of those intricacies, especially when listening to a performance without a score?

As a habitual perpetrator of notational niceties of the sort under discussion, I must say that this line of argument (which comes up often) baffles me. It presumes that the listener "should", in an ideal world (presuming a perfect memory and an absolutely accurate performance), be able to reconstruct a score. I don't see why this is (a) necessary (b) desirable; but the suggestion that it is neither tends to elicit a huge amount of conceptual resistance, even from those whom I had thought would be sympathetic. I'm just now finishing up a piece that, notationally, involves a good deal of rhythmic intricacies; simultaneously, the (solo) performer is instructed to use a great deal of free rubato. This will, presumably, thoroughly negate the ability of a listener to reconstruct the rhythmic notation, but I can't say I care. I'm much more interested in the overlapping and nested rhythmic frames being used as a notional regularity (or, more aptly, unordered collection of regularities) that serves at least as much as a starting point for an effective performance as it does its end. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #56 on: 14:21:41, 23-04-2007 » |

|

whereas I think that there is also from time to time the additional problem for the listener that, even when the performer has mastered such rhythmic intricacies as well is as humanly possible, there remains the question as to the extent to which even the most aurally adept listener may be expected consistently to attune him/herself accurately to the precise nature of those intricacies, especially when listening to a performance without a score?

As a habitual perpetrator of notational niceties of the sort under discussion, I must say that this line of argument (which comes up often) baffles me. It presumes that the listener "should", in an ideal world (presuming a perfect memory and an absolutely accurate performance), be able to reconstruct a score. I don't see why this is (a) necessary (b) desirable; but the suggestion that it is neither tends to elicit a huge amount of conceptual resistance, even from those whom I had thought would be sympathetic. I'm just now finishing up a piece that, notationally, involves a good deal of rhythmic intricacies; simultaneously, the (solo) performer is instructed to use a great deal of free rubato. This will, presumably, thoroughly negate the ability of a listener to reconstruct the rhythmic notation, but I can't say I care. I'm much more interested in the overlapping and nested rhythmic frames being used as a notional regularity (or, more aptly, unordered collection of regularities) that serves at least as much as a starting point for an effective performance as it does its end. I am not advocating, as such, that listeners should all be able at all times to reconstruct a score from memory; for one thing, almost no listener could do that in most cases and, in any event, music is not generally intended for listening only by those who are musically literate (i.e. capable of reading a score); what I do say, however, is that I wonder if, the more complex the nature of certain rhythmic intricacies, the less certainty of their accurate realisation in performance the listener might derive from listening to them. In cases where the perceptible detail reduces below a certain extent even for the most adept listener, one might begin to wonder if certain of the notational conventions used in the score are more complex than is necessary for the purpose of putting across the composer's thoughts and intentions; the only trouble with this "argument" is, as I've implied before, where one can reasonably expect to draw the line in this regard, but I think that the issue nevertheless inhabits the rather wider world of the extent to which, in certain cases, the individual composer is him/herself able to hear, in his/her mind's ear and/or in performance, the full details of his/her work as written. Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 15:41:02, 23-04-2007 by ahinton »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #57 on: 15:22:20, 23-04-2007 » |

|

what I do say, however, is that I wonder if, the more complex the nature of certain rhythmic intricacies, the less certainty of their accurate realisation in performance the listener might derive from listening to them. In cases where the perceptible detail reduces below a certain extent even for the most adept listener, one might begin to wonder if certain of the notational conventions used in the score are more complex than is necessary for the purpose of putting across the composer's thoughts and intentions; I think this may be the wrong way to conceive of the role of the score - rather than 'putting across the composer's thoughts and intentions', I prefer to think of it as delineating the range of possibilities for the performer. The use of a high degree of rhythmic detail in such a score, instead of prescribing a particular effect, has to do with directing the performer away from more habitual modes of performance. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

time_is_now

|

|

« Reply #58 on: 15:37:33, 23-04-2007 » |

|

One of the things that I always find striking is the number of composers, writing quite a range of different styles and at quite varying degrees of complexity/specification of parameters etc., is how many of them claim to be writing 'as simply as I can without betraying my style', etc. etc. Do posters here think this is a case of feeling obliged to talk down their difficulty so as not to be accused of making life unnecessarily hard for performers or listeners? Is it based on an assumption that economy of means is desirable - and how valid is such an assumption (or how meaningful, when some of the music it leads to is still highly 'complex' by any normal standards)? Or is something else at stake?

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

The city is a process which always veers away from the form envisaged and desired, ... whose revenge upon its architects and planners undoes every dream of mastery. It is [also] one of the sites where Dasein is assigned the impossible task of putting right what can never be put right. - Rob Lapsley

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #59 on: 15:40:34, 23-04-2007 » |

|

what I do say, however, is that I wonder if, the more complex the nature of certain rhythmic intricacies, the less certainty of their accurate realisation in performance the listener might derive from listening to them. In cases where the perceptible detail reduces below a certain extent even for the most adept listener, one might begin to wonder if certain of the notational conventions used in the score are more complex than is necessary for the purpose of putting across the composer's thoughts and intentions; I think this may be the wrong way to conceive of the role of the score - rather than 'putting across the composer's thoughts and intentions', I prefer to think of it as delineating the range of possibilities for the performer. You are absolutly correct and I agree with you, for this is what I meant and I should therefore have written "...for the purpose of enabling the performer/s to put across..." The use of a high degree of rhythmic detail in such a score, instead of prescribing a particular effect, has to do with directing the performer away from more habitual modes of performance.

I'm not quite sure that I understand what you mean by this, or indeed the specific kinds of context in which you see it as being applicable; I have always though and hoped that the degree of detail in a score ought to help the performer (as far as possible) grasp the composer's intentions rather than leading him/her "away" from things other than those intentions (if you see what I mean!)... Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|