In response to a post from Reiner on the postmodernism thread:

Well, perhaps you could first tell us in which work (with bar-numbers, please) we can hear "Palestrina" in Brahms's work?

I'm not saying we can hear Palestrina, but that he may have derived some musical ideas from his study of Palestrina's work. Here are the opening bars (bars 1-11, to be precise) of the second movement of Brahms's First Piano Concerto in D minor Op. 15:

And here is the opening of the Kyrie from Palestrina's

Missa Papae Marcelli:

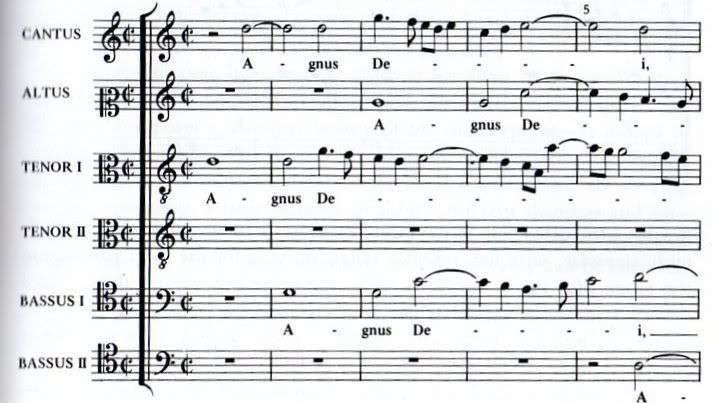

and here is the opening of the Agnus Dei I (with a similar motive to be found at the beginning; this recurs in other movements)

Now, Brahms knew the latter work intimately, having studied it intensely in 1856 (he wrote the First Piano Concerto in 1856-59) and copied it out. That opening motive, with a rising fourth then a stepwise descent, recurs continuously in the Palestrina. I am personally quite sure that, bearing in mind the proximity of his study and the composition of the work, he drew upon the Palestrina when creating his own theme. There are other works from the same period which clearly show the Palestrina influence (such as the

Geistliche Chore Op. 37 of 1859), which I don't have to hand at the moment, but can also post on here at some point if you would like.

Now, you might think this is a reference so deeply absorbed and modified that the resemblance becomes of little consequence. That may be true, but the point is to demonstrate how Brahms absorbed and individuated his many influences.

Then I'll dig out his cod chorale for you

Please do - I'd like to know where it is.

Unlike you, I do not believe that ANY composer is "above challenge", and I don't put composers on pedastals as you do. Nor, frankly, do I accept "I know better than you do" as a line of argument.

I'm not sure if this comment was addressed to Alistair or I. I certainly don't believe any composer to be 'above challenge' either (indeed, am often critical of various artistic sacred cows, such as Oscar Wilde, for example?

), but would appreciate some more detail on these questions, that's all. It seems that the major case against Brahms have to do with him using a Lutheran chorale in the last movement of a piano concerto, and not having any aptitude for writing for the stage.

Actually, I have blown hot and cold on Brahms over the years (went through a long period in my 20s where I was completely off him), and can understand the reasons why some would not be drawn to him (I can elaborate on these later in this thread, perhaps). But I think criticism can at least deal with specifics as well as generalities.

I find there is nothing a Protestant German writing for the comfortable bourgeousie in the cosy economic certainties of late C19th Vienna

Well, there were an awful lot of very different Protestant Germans. And as I say, Brahms was not particularly religious at all. He gained some financial security at a certain point in his life, but it wasn't always like that. And as for writing for the 'comfortable bourgeoisie', obviously I agree that's a factor, but one that could be said of just about any 19th-century (and, indeed a good deal of 20th-century) composers, rather than being specific to Brahms.

has to say to me as an Atheist Brit Expat living in a country in the hairlines of American ballistic missiles. (Still less a devout Catholic organist from provincial Austria [Bruckner]).

Well, in the case of Bruckner, how do you think his devout Catholicism is manifested in his music (I'm not saying it isn't)? And how would it compare, say, to that of the equally devout Catholic (at least in his later years) Liszt?