|

Chafing Dish

Guest

|

|

« Reply #30 on: 23:40:12, 05-05-2007 » |

|

I am most taken by the Walter Frisch observation about Sym 2/iii -- the individual sections do seem like the 'Alio modo' passages in Frescobaldi (same melodic pattern, new meter and/or rhythmic pattern). See Fresco's Bergamasca or Cento Partite. A very arcane reference, even for Brahms (if intended).

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #31 on: 23:41:23, 05-05-2007 » |

|

A letter written from Brahms to Joachim in January 1886, accompanying his sending of the manuscript of the Fourth Symphony, might be of interest in this context:

I have entered some tempo modifications in pencil into the score. They may well be useful, even necessary, for a first performance. Unfortunately they thereby often find their way into print - with me and with others - where they mostly do not belong.

Such exaggerations are only really necessary as long as a work is unknown to the orchestra (or soloist). In that case I often cannot do enough pushing forward and holding back, so that passionate or calm expression is produced more or less as I want it. One a work has got into the bloodstream, there should be no more talk of such things in my view, and the more one departs from this [rule], the more inartistic I find the performing style.

I experience often enough with my older things how everything goes so completely by itself, and how superfluous much marking-up of this type is! But how people like to impress these days with this so-called 'free artistic' performing style - and how easy that is with even the worst orchestra and just one rehearsal! An orchestra like the Meiningen should take pride in showing the opposite!

|

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 23:44:15, 05-05-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #32 on: 23:43:53, 05-05-2007 » |

|

I am most taken by the Walter Frisch observation about Sym 2/iii -- the individual sections do seem like the 'Alio modo' passages in Frescobaldi (same melodic pattern, new meter and/or rhythmic pattern). See Fresco's Bergamasca or Cento Partite. A very arcane reference, even for Brahms (if intended).

Wow, that's quite a find. Brahms definitely knew Frescobaldi's work; he owned scores of it. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

quartertone

|

|

« Reply #33 on: 00:04:48, 06-05-2007 » |

|

It's also worth noting that the melody that opens the 3rd movt of the 2nd symphony is a (transposed) inversion of the double bass motive that opens the first.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #34 on: 00:07:51, 06-05-2007 » |

|

It's also worth noting that the melody that opens the 3rd movt of the 2nd symphony is a (transposed) inversion of the double bass motive that opens the first.

Absolutely - that figuration is recurrent through the symphonies, appearing in the big tune of the last movement of the first, and the last movements of the second and third as well. The slow movement of the fourth could be seen as an extension of it (again in inversion), also. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

thompson1780

|

|

« Reply #35 on: 00:56:41, 11-05-2007 » |

|

[How come there are so many threads on this forum that I read, then forget about? Anyway, finally stumbled across this one again, and got round to (speed) reading it]

I can't believe that no one has mentioned the length of line in Brahms - for me that is one of the characteristics of his works that makes it so recognisable. Perhaps the closest is the comment made that Brahms chastised R Strauss for not enough 8 bar melodies.

Brahms seems to go "long - long - verrryyyy looong" is his phrases a lot. (e.g. phrase, then equally long answering phrase, then a super long phrase which combines elements of both initial and answering phrases). The example that's going in my head at the mo is the second movement of the double concerto.

I love the really extended bits, and get annoyed when performers chop up Brahms.

Tommo

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

Made by Thompson & son, at the Violin & c. the West end of St. Paul's Churchyard, LONDON

|

|

|

|

Chafing Dish

Guest

|

|

« Reply #36 on: 02:07:45, 11-05-2007 » |

|

I can't believe that no one has mentioned the length of line in Brahms - for me that is one of the characteristics of his works that makes it so recognisable. Perhaps the closest is the comment made that Brahms chastised R Strauss for not enough 8 bar melodies.

Brahms seems to go "long - long - verrryyyy looong" is his phrases a lot. (e.g. phrase, then equally long answering phrase, then a super long phrase which combines elements of both initial and answering phrases). The example that's going in my head at the mo is the second movement of the double concerto.

I love the really extended bits, and get annoyed when performers chop up Brahms.

Tommo

We didn't touch on that explicitly, true: but I now have looked a little further into the link btw Brahms and Frescobaldi, tenuous as it may be. The following Frescobaldi pieces were in Brahms's handwritten collection (via Revue Musicologique accessed through JSTOR): the Partite sopra l'Aria detta la Romanesca (just the first part) a Toccata from Fiori Musicali (one of those labelled alla Levatione - but not sure which one) the Toccata #12 (from the first Book of Toccatas, I assume, since the 2nd book only contains 11) and the long-toothed Aria detta la Frescobaldi [sic] That is surely not an exhaustive list of pieces that Brahms KNEW, but just the ones he hand-copied. I am also not yet sure whether the numbers or titles were errors, but there's no reason to think so. Back to what you said, Tommo: all these 'models' contain long phrases that don't respond well to being 'chopped up' -- only their hierarchies are certainly nowhere near as clear as the Brahms phrase you describe (antecedent and consequent ideas, Fortspinnung, etc). That kind of contrast was not a desideratum in early 17th century Italy! Anyway, I intend to play through these pieces over and over and try to pretend I am [listening to] Brahms. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Sydney Grew

Guest

|

|

« Reply #37 on: 03:57:48, 11-05-2007 » |

|

I can't believe that no one has mentioned the length of line in Brahms - for me that is one of the characteristics of his works that makes it so recognisable. Perhaps the closest is the comment made that Brahms chastised R Strauss for not enough 8 bar melodies. As Mr. Smittims has already pointed out, Schoenberg, particularly in his essay " Brahms the Progressive", has much that is illuminating to say. Relevant here are his sections 10 to 15 (24 pages in all) of that essay. They discuss " asymmetry, irregularity, and imparity in the number of bars" in Brahms and many other composers; a great many musical examples are included, as is a discussion of Brahms' setting of metrically irregular verse. (And yes he is is saying that Brahms wrote fewer eight-bar melodies than other composers, is he not?) But this is Schoenberg's most interesting point - it concerns "the remoteness of a genius's foresight": "The most important capacity of a composer is to cast a glance into the most remote future of his themes or motifs. He has to be able to know beforehand the consequences which derive from the problems existing in his material, and to organize everything accordingly. . . . Thus one must not be astonished by an act of genius when a composer, feeling that irregularity will occur later, already deviates in the beginning from simple regularity. An unprepared and sudden change of structural principles would endanger balance."

As we have often pointed out, a work of Art has to be an organic and balanced whole in which everything references as much of everything else as it possibly can, given the nature and limitations of the medium - that is what he is in part here saying. Sometimes we feel that the later Schoenberg did better as writer than as composer! |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #38 on: 04:51:59, 11-05-2007 » |

|

Sometimes we feel that the later Schoenberg did better as writer than as composer!

Somehow "we" could see that one coming, from your corner; it was only a matter of time... Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #39 on: 10:35:36, 11-05-2007 » |

|

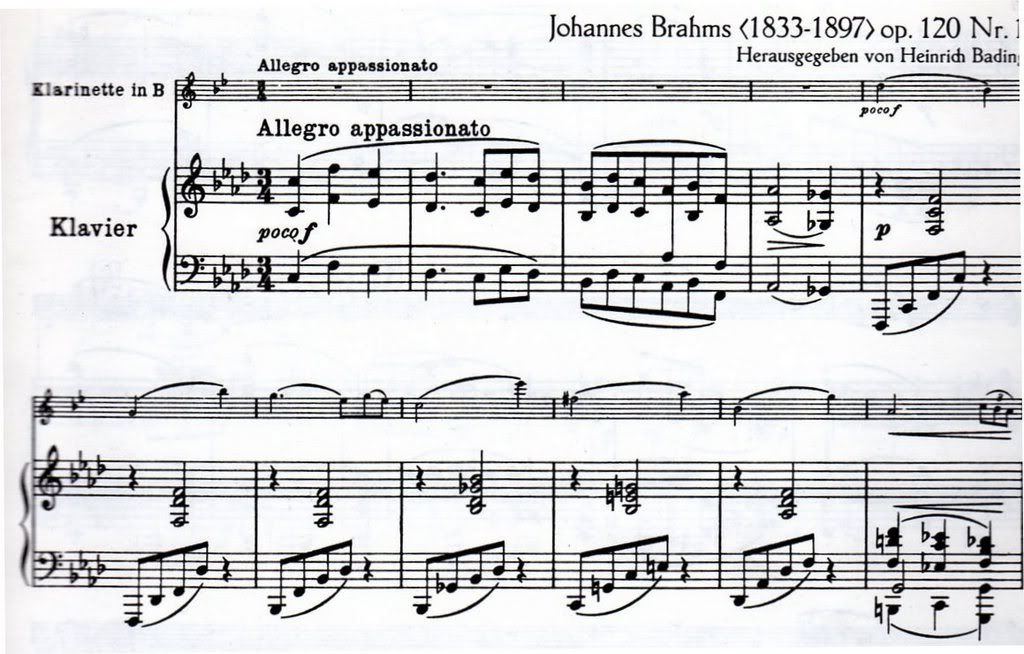

I love the really extended bits, and get annoyed when performers chop up Brahms. Hm. You probably wouldn't like my Brahms much then.  Personally I'm certainly one for articulating those long lines, mainly because that's very often what he wrote. (And said he wanted in his correspondence with Joachim, which Ian will doubtless have to hand.) Particularly close to home for me are the clarinet sonatas of course - the first clarinet entries of both have a succession of slurs of varying lengths which in the case of the F minor points up the construction of the melody (from one of those typically Brahmsian chains of thirds). They also give the line a swing which goes perfectly with the piano part - and when the piano plays the same music later you actually have to contravene the text if you're not going to articulate the bars since he's put staccato marks on the last chord of the slur. I think there's a rather important distinction between articulating the sound and 'chopping up' the line - musical continuity isn't necessarily the same thing as continuous sound... |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

trained-pianist

|

|

« Reply #40 on: 10:38:23, 11-05-2007 » |

|

I played clarinet sonatas with viola ollie. I thought they are wonderful.

I have to look at them again.

I think they are better done by clarinet. May be clarinet was a first choice. But they are good with viola too. I forgot if I played one sonata or more. I have such a bad memory.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

smittims

|

|

« Reply #41 on: 10:48:31, 11-05-2007 » |

|

'Sometimes we feel that the later Schoenberg did better as writer than as composer!'

Schoenberg was indeed a very fine and illuminating writer in old age. I'm just re-reading 'Brahms the Progressive'. Such insights into Mozart as well.

But valuable as they are , his writings are trivial in comparison with his late masterpieces of composition .

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #42 on: 11:01:37, 11-05-2007 » |

|

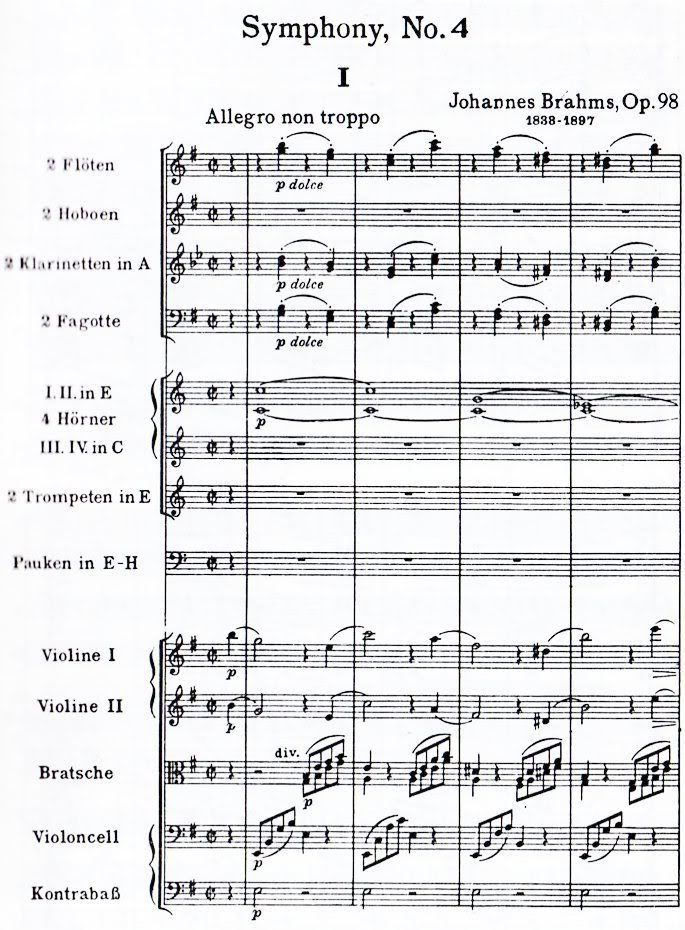

I love the really extended bits, and get annoyed when performers chop up Brahms. Hm. You probably wouldn't like my Brahms much then.  Personally I'm certainly one for articulating those long lines, mainly because that's very often what he wrote. (And said he wanted in his correspondence with Joachim, which Ian will doubtless have to hand.) Particularly close to home for me are the clarinet sonatas of course - the first clarinet entries of both have a succession of slurs of varying lengths which in the case of the F minor points up the construction of the melody (from one of those typically Brahmsian chains of thirds). They also give the line a swing which goes perfectly with the piano part - and when the piano plays the same music later you actually have to contravene the text if you're not going to articulate the bars since he's put staccato marks on the last chord of the slur. I think there's a rather important distinction between articulating the sound and 'chopping up' the line - musical continuity isn't necessarily the same thing as continuous sound... Brahms made clear his preference that two-note slurs be played according to earlier conventions, by which the second note is shortened and successive groups are thus separated by a short rest, in a letter to Joachim of 30 May 1879. It is included in the chapter 'Joachim's violin playing' by Clive Brown, in Michael Musgrave and Bernard D. Sherman (eds) - Performing Brahms: Early Evidence of Performance Style. I have located four other pieces of corroborating evidence for Brahms's preferences in this respect, which will appear in my book. Brahms scholars are generally in agreement on this point (for what that's worth). The example to which Ollie draws attention, from the Clarinet Sonata Op. 120 No. 1:  can be compared with the opening of the Fourth Symphony:  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

trained-pianist

|

|

« Reply #43 on: 11:08:21, 11-05-2007 » |

|

Ian, can you talk about another sonata? I don't think I played this one.

Although it is good for me to look at this sonata too. Thank you for posting.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #44 on: 11:19:04, 11-05-2007 » |

|

We didn't touch on that explicitly, true: but I now have looked a little further into the link btw Brahms and Frescobaldi, tenuous as it may be. The following Frescobaldi pieces were in Brahms's handwritten collection (via Revue Musicologique accessed through JSTOR): Was that E. Kern's article Brahms et la musique ancienne from 1942 (my access to JSTOR is slightly limited from this computer, so can't download it right now)? Often a way of ascertaining how deeply Brahms knew certain works is by looking at whether he made markings in them in his library. I'll ask the director of the Brahms Gesellschaft about the other Frescobaldi works you mentioned. Incidentally, another article well worth reading on Brahms and early music is Elaine Kelly - 'An Unexpected Champion of François Couperin: Johannes Brahms and the ‘Pièces de Clavecin’ ' in Music and Letters 2004 85(4):576-601. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|