|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #60 on: 18:53:09, 30-04-2007 » |

|

... (I think) there's no analogy in music for "suspension of disbelief" - music can present itself not as something being portrayed (though it can do this as well), but as the something itself.

This statement is, I take it, excepting vocal works? Well, excepting vocal works with a theatrical element. A question I often ask myself when watching operas, particularly recent ones, that is to say from a period in history in which the pull of convention is weaker or absent, is "why are they singing?" Which isn't to say that there couldn't be a reason, but recently I finally got started on listening to Peter Grimes, and the first scene kept that question in my mind almost constantly - it seemed to me there was nothing in the scene which couldn't have been more clearly and powerfully projected if the music were left out. Harsh words, I know, and I'm prepared to be converted if I ever get past this scene, but it sounded to me that all Britten was doing was combining commonplace vocal lines with a rough-and-ready accompaniment in order just to fill the time out with music. Well, that's a question I ask in the context of operatic works as well. But in the case of the first scene of Peter Grimes, I do feel there's more to it. It is somewhat in the manner of a more fleshed-out recitative at first (the whole scene is necessary in order to put the subsequent events in context), so that the moments when the music add an extra perspective are all the more striking. Swallow's vocal writing surely adds considerably to the impression of his pomposity, especially with those rather overwrought angular lines where he sings the opening melody ('Peter Grimes I here advise you...'). Grimes's own lines are consistently accompanied by sustained string chords, the idea for which surely came from the similar treatment of Christ's singing parts in Bach's St Matthew Passion. These contrast strongly with the surrounding music, and communicate something of the martyr-like figure that Grimes will come to represent. The sense of the 'lone individual against the crowd' is quite overwhelming in this scene, with only Grimes given any sort of more sensitive characterisation, most of the other characters (nearly all of whom make an appearance in this prologue) merely caricatures. This aspect of Britten's writing was something that put me off for a while, but closer listening reveals that it is just the way he introduces people, giving some sense of the way they can be observed as grotesques from the outside. Most of them are developed quite significantly and subtlely through the course of the opera, revealing more dimensions than the original caricatures might suggest. Various motives which will be later developed throughout the opera are also introduced in this prologue (for example the F-B-flat-A-B-flat for the crowd, which recurs at several points, most tragically in Grimes's final mad scene, also the rising ninth which always symbolises Grimes's forlorn dreams). There is a lot going on in this scene which might seem less significant when taken on its own, but is essential to the whole work, and which could not in my opinion be conveyed just by the words. Do keep listening! By the way, the 'rough-and-ready' quality of the music surely plays a part in communicating what a farcical affair this inquest is, doesn't it? (I've copied this stuff into the 'Barrett on Grimes' thread, by the way) |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 19:07:33, 30-04-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #61 on: 18:56:02, 30-04-2007 » |

|

... (I think) there's no analogy in music for "suspension of disbelief" - music can present itself not as something being portrayed (though it can do this as well), but as the something itself.

This statement is, I take it, excepting vocal works? Or works with clearly descriptive, programmatic, or narrative elements made explicit through title or programme notes? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

TimR-J

Guest

|

|

« Reply #62 on: 19:32:57, 30-04-2007 » |

|

I wonder about this suspension of disbelief question. If we are to take it literally then I would, cautiously, agree with those posters who say that since music is basically non-representative 'suspension of disbelief' is not possible in music.

BUT

I take SoD in the theatre to mean a more complex process than the simple engagement of a 'what we're watching isn't real' switch in the brain. Remaining in the theatre, this process is associated with assorted dramatic devices - a raising curtain, a prologue, the house lights going down, all sorts things scripted and simply practical - that draw the mind into an altered mode of perception appropriate to watching, and enjoying, a play (call it an aesthetic state or somesuch if you wish). In fact, I think SoD is but one aspect of this state (others have, perhaps, to do with altered modes of listening - for rhythm/rhyme, eg - an altered and flexible concept of time, etc, etc), and that the state, in general, can (should) be applied across the arts. The general state is something to do with drawing a (mental) line between real life - which is full of people walking around, talking to one another - and the theatre - which is full of people walking around, talking to one another.

So, when sitting to listen attentatively (and this suggest for me a wide range of attitudes such as have already been suggested upthread) to a piece of music we go through a series of actions - partly physical, partly mental, partly guided by the gestures of the music itself - that distinguish the sounds we hear before the first downbeat, and the sounds we hear afterwards (even 4'33" very carefully makes this distinction). It's not quite suspension of disbelief, but it is, I think, an analogous act - a suspension of reality of some sort.

(Before I find myself in a can of worms, I should add that I don't have a sort of positivistic intent to extract all 'reality' from art and tend towards something, well, 'absolute'. Rather, I think it's a pretty undisputable fact that anything from 'reality' brought into the realm of an artwork is altered - enriched - in some way simply through the processes I outline above. Art can retain a groundedness in the dirt of real life, but simply by being art it is something other than real life too.)

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #63 on: 19:38:12, 30-04-2007 » |

|

On the 'realism' question, I laughed a bit when I read the following bit from Terry Eagleton: 'If a representation were to be wholly at one with what it depicts, it would cease to be a representation. A poet who managed to make his or her words 'become' the fruit they describe would be a greengrocer.' (from a review of Erich Auerbach's Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, at http://www.lrb.co.uk/v25/n20/eagl01_.html ) Similarly, if Messiaen's birdsongs actually became thoroughly at one with what he depicts, than he would be the keeper of a bird sanctuary? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

increpatio

|

|

« Reply #64 on: 19:42:34, 30-04-2007 » |

|

... (I think) there's no analogy in music for "suspension of disbelief" - music can present itself not as something being portrayed (though it can do this as well), but as the something itself.

This statement is, I take it, excepting vocal works? Or works with clearly descriptive, programmatic, or narrative elements made explicit through title or programme notes? This seems like a non-trivial generalization; when people are playing programme music, what is required is an understanding of the themes &c; for instance, if someone is playing a motif to represent a spoon, you don't need to feel the player to actually be a spoon, but rather understand that the music represents a spoon, but with (theatrical) singing, the person is actively acting like X, and it contributes enormously if you can just imagine them as being X. Of course both parts, as TimR-J mentioned, seem to require some general change of mind-set. (unless one understands a "programme" as being an elaboration of the traditional musical notion of "form"; but maybe that's a bit roundabout...). Ian...managed to slip in another post before I got in! That image of Eagleton's is rather funny...and relates to what I just said...but...I think I'll have to sleep on it to work it out : ) |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 19:45:56, 30-04-2007 by increpatio »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

roslynmuse

|

|

« Reply #65 on: 21:07:46, 30-04-2007 » |

|

I like Tim's remark - "SoD is but one aspect of this state (others have, perhaps, to do with altered modes of listening - for rhythm/rhyme, eg - an altered and flexible concept of time.)" I wonder whether indeed the whole way that our perception of the passage of time changes when we listen to music is the musical equivalent of SoD in the theatre, and why vocal works - whether song, choral or opera - work on a different level to instrumental music. Furthermore, it may be that the opera buff who likes his Verdi and Puccini, some Mozart, not a lot of Wagner and very little of the C20th century repertoire is in fact responding only to the dramatic, theatrical SoD conventions and that musical considerations (and the combination of demands of responding to text AND music) are relegated to some sort of background.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

TimR-J

Guest

|

|

« Reply #66 on: 10:21:04, 01-05-2007 » |

|

Roslyn - I think the perception of time (be it in music or on the stage) is definitely an important part of that altered state. This is clear in the theatre, when we quite happily accept that it is morning one moment, and evening the next, or that two things are happening in sequence on stage, but simultaneously in the realm of the story, and so on. I think the processes by which music warps time - so that there is a musical time that is not quite the same as clock time - are similar, although much harder to identify precisely.

Vocal works, I suspect, do behave a little differently to purely instrumental music, in that I would suggest that the combination of a 'musical time' and a 'textual (even theatrical) time' adds a level of complexity. So the music may be running to a similar temporal stream as the text; but - and I would suggest that the better vocal/dramatic settings do this more often than not - it operates on its own stream, which somehow compliments that of the text. (Music that too closely follows its text is more like cliched film music.) So, to give a crude example, a strophic song doesn't have to have new music for every verse, even as the text is different each time: there's a textual temporal stream that moves at varying pace forwards through a narrative; accompanied by a musical stream that cycles back and forth between verse and chorus. (A very crude example, but hopefully you see what I'm getting at.) In the process of listening, we engage with both these 'times', neither of which have anything to do with the passing minutes in which we sit listening.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

roslynmuse

|

|

« Reply #67 on: 10:42:02, 01-05-2007 » |

|

Tim - thank you for a very clear exposition of what I was trying to say! I agree entirely. (I especially agree with the cliched film music ref - one of the reasons why Britten, for me, so often fails to get off the ground.)

The question that interests me is - why does the passage of time seem to slow down with certain types of music and speed up with others? (I don't think it is as simple as a relationship with tempo, harmonic rhythm or even dynamics.) Is it simply a perception on the part of the individual listener or is it an effect of the music itself (and therefore, how do different performances affect one's perception?)

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

marbleflugel

|

|

« Reply #68 on: 18:16:19, 02-05-2007 » |

|

Not an answer, Ros, but Stan Tracey wrote a piece called Timespring. What I think subjectively his idea in this

implies is that you can get the feel of extending or winding in a moment. Tippett was latterly fascinated by the

rythmn of television (not the progs but the editing of shots) as analogous to pacing symphonic/ operatic 'time'.

You might be able to trace to archetypal inter-relations in various languages and onomatoepeia as Chomsky/ Bernstein suggested in a roundabout way, or Jackman's Conversation Analysis/ Ethnic equivalents. Bit of a grab-bag of stuff out there, but I suspect its a variegated combination effect? And there's that poem by Roethke where he says of an old girlfriend 'I measure time by how a body sways'. I'll get me coat.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'...A celebrity is someone who didn't get the attention they needed as an adult'

Arnold Brown

|

|

|

|

George Garnett

|

|

« Reply #69 on: 18:02:24, 24-06-2007 » |

|

Since we're all friends here, I'll risk a few more naive questions prompted by various discussions on these boards. They probably get dealt with in the first week of GSCE Music but that's never stopped me asking before....

1. This word 'gesture' as in 'musical gesture'. I have a rough idea of what it means but does it have a specific technical meaning in musicology? Is it meant to be a read across into musicology from the same term in semiotics (which would seem to me problematic) or is it being used quite differently? It sometimes seems to be used in contrast to 'melody'. Does that imply that it is a generic term for what might also be called a motif, or a cell, or am I cheerfully barking up the wrong tree again?

2. Mediation. I've gathered (principally from Ian) that for a composer to 'mediate' existing musical ideas is a good thing and failing to mediate them is a bad thing but what is actually meant by that? I take it that 'mediation' is not the same as 'assimilation' but it nonetheless has something to do with the composer digesting and transforming material into his or her own creative language. Is that very roughly it? But if so, why the insistence that this must be done for a piece to be successful? Couldn't deliberately refusing to 'mediate' for particular artistic purposes be legitimate as well?

3. When does 'timbre' turn into 'texture'? Are they on a continuum or are they different in kind? Is it just a matter of 'timbre' being a property of a single instrument with 'texture' involving combinations of several, or is that too simple?

|

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 17:15:20, 08-09-2007 by George Garnett »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #70 on: 19:03:02, 24-06-2007 » |

|

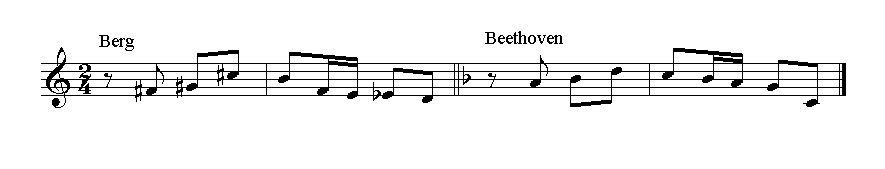

Since we're all friends here, I'll risk a few more naive questions prompted by various discussions on these boards. They probably get dealt with in the first week of GSCE Music but that's never stopped me asking before.... Hi George. Nothing 'naive' about these questions, they are a suitable rejoinder to some of us in case we use jargon in a cavalier fashion without first defining it adequately both for ourselves and others! So.... 1. This word 'gesture' as in 'musical gesture'. I have a rough idea of what it means but does it have a specific technical meaning in musicology? Is it meant to be a read across into musicology from the same term in semiotics (which would seem to me problematic) or is it being used quite differently? It sometimes seems to be used in contrast to 'melody': does that imply that it is a generic term for what might also be called a motif, or a cell, or am I cheerfully barking up the wrong tree again? Gesture is a word that in my experience is used more frequently by composers than musicologists. Basically it defines a small phrase or phrase unit, usually with a quite distinctive shape. It is most applicable in music which employs contrasting short phrases, thus contrasting gestures. A 'cell' would be a slightly ambiguous term to use, as a cell can mean something on a more microscopic level which is not necessarily so visible on the surface or clearly individuated from that which surrounds it (for example a rhythmic cell). A 'motif' suggests something that in some sense recurs or is developed, which is not necessarily the case (though frequently it is) with a gesture. 'Melody' can imply something longer and more mellifluous, for which the term 'gesture' may not be appropriate. The term 'gesture' is useful in dealing with certain late modernist, post-serial, music which presents abstracted musical 'shapes' or contours, which resemble those from earlier music but without necessarily having the same harmonic basis as they once did. An example would be that below, from Berg's Wozzeck a gesture believed (at least by some) to be abstracted from that in Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony:  In terms of semiotics, that field has made some inroads into musicology in two different but related manners. There is a school of semiotic analysis of music (the key text for which is Jean-Jacques Nattiez's Music and Discourse), an elaborate means of performing analysis based upon low-level gestures treated in a manner akin to signs, and also a New Musicological application more loosely of semiotics in the sense of placing emphasis upon the supposed signifying power of certain musical archetypes (an example would be the use of drone harmonies, upper neighbour note embellishments, the use of drums and cymbals, etc., to signify 'Turkey' in various 18th century music). But both of these schools seem rather over-eager to directly transfer paradigms concerned mostly with literature, to the much more semantically ambiguous and sometimes stylistically mellifluous medium of music. 2. Mediation. I've gathered (principally from Ian) that a composer to mediate existing musical ideas is a good thing and failing to mediate them is a bad thing but what is actually meant by that? I take it that 'mediation' it is not the same as 'assimilation' but it nonetheless has something to do with the composer digesting and transforming material into his or her own creative language. Is that very roughly it? But if so, why the insistence that this must be done for a piece to be successful? Couldn't deliberately refusing to 'mediate' for particular artistic purposes be legitimate as well? Mediation is perfectly well encapsulated by your definition of 'the composer digesting and transforming material into his or her own creative language'. The issue of the value or otherwise of mediation comes up especially in the context of neo-romantic, post-modern, or other highly 'referential' music. This is a major faultline separating highly opposing schools of aesthetic thought: from the postmodernist position, a relatively 'unmediated' use of musical 'found materials' signifies some statement of compositional modesty (this is tied up with feminist critiques of male composition as representing ego above all), an acknowledgement of the 'decenteredness' of the compositional self (which is itself formed at least in part by external influences, including other music), and enabling a supposed 'intertextuality', so that a work can interact with that external to itself rather than supposedly presenting a hermetically sealed world. From the modernist position (and especially from a leftist modernist position), the very lack of mediation in some music signifies the impersonalisation of contemporary composition, by which the composer is reduced to a merely functional role with little place for their own subjectivity. An Adornoesque critique (of the type that has been extensively developed by later thinkers in Germany, including in the context of debates on postmodernism) would argue that this parallels the plight of the individual under the impersonal forces of late capitalism. But there are more sophisticated perspectives on relative unmediation in past works, as can be found, say, in Adorno's book on Mahler (the 'subjectivity' he privileges is not necessarily the same as simple individual will and desires, but has sometimes to do with what he conceives in a rather grandiose manner as 'the subject of history' - in Mahler he argues that the individual subject takes a back seat, but the 'subject of history' continues to march on - this is a complex argument which I won't elaborate further on here). Mediation is often seen as the most direct manifestation of subjectivity. Of course it can take various forms - in Berio's Sinfonia, for example, whilst most of the material is presented in relatively unaltered form in terms of comparing a fragment with the passage from where it comes in his various sources, still the manner of 'cutting it up', superimposing or juxtaposing different fragments is itself a highly mediatory process. 3. When does 'timbre' turn into 'texture'? Are they on a continuum or are they different in kind? Is it just a matter of 'timbre' being a property of a single instrument with 'texture' involving combinations of several, or is that too simple? Texture is not a term generally used for a single monophonic instrument; in the case of the piano, say, it is (because one can create 'textures' through different types of material in various registers). But 'timbre' can be something that is a property of a group of instruments rather than just a single one - one can speak of 'orchestral timbre', for example. The difference between the two terms in this context is somewhat ambiguous: it may be simply a matter of 'timbre' seeming a more 'scientific' term (as something that can be measured and analysed in detail), whereas as 'texture' relates to a more informal perception. There is of course also the term 'colour', of which I'm not fond, primarily because it is so often strongly attached to certain types of value judgements, certain types of textures/timbres being defined as having 'colour', others as not, the implication being that 'colour' in this sense is always a good thing. So some would say that an orchestral work of Knussen has 'colour', whereas Stockhausen's Gruppen does not (despite the variety of timbre contained therein). |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 19:13:41, 24-06-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

richard barrett

Guest

|

|

« Reply #71 on: 19:35:50, 24-06-2007 » |

|

Yes indeed.

I have a couple of cents' worth of my own to add though.

Gesture - I think there's some mileage in taking the word at face value, that is to say it's a musical event whose nature (or at least whose timescale) is related to that of a single bodily movement (ie. "gesture" in the usual sense).

Mediation - I've always used this word in a different sense, particularly when I describe a form of musical expression or experience as "unmediated", by which I mean (more or less) "direct", without so to speak "anything getting in the way". I must confess I've never previously come across the meaning which both Ian and George are conversant with. (I never said I was clever though!)

Timbre/texture - for me it's a question of timescale, timbre being a quality of sound which (like pitch) is heard and recognised immediately, texture a more complex quality which (like rhythm) requires some time to be recognised.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #72 on: 19:59:26, 24-06-2007 » |

|

I think your definition of 'mediation', Richard, is compatible with mine, as you refer to the listening experience, whereas I'm referring to something somehow intrinsic to the work, to do with its relationship to a wider musical language and other works. So it may be possible to have a piece of music which exhibits a high degree of compositional mediation (this rests upon the assumption that composers are in general not creating their musical language 'from scratch', so they inherit something which they can then mediate), but that the resulting work can be heard in an 'unmediated' manner on the part of the listener. As if it weren't complex enough.....  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

richard barrett

Guest

|

|

« Reply #73 on: 20:11:05, 24-06-2007 » |

|

Thanks, that's all clear now!

Did I really say that?

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

roslynmuse

|

|

« Reply #74 on: 20:53:29, 24-06-2007 » |

|

Can I add a further thought re texture/ timbre; I always think of (and use) the word timbre to refer to the sound of an instrument/ voice/ any combination thereof; and use texture to refer to its application to a particular type of passage ie including the notes which may or may not include gestures (or cells or motifs, although probably not melodies...) Or perhaps, since one cannot totally dissociate timbre from notes, with texture the emphasis is more on the notes and their patterns, and with timbre with the particular combination of sounds.

Oh dear, the more one tries to define, the more difficult it gets.

Anyone like to offer any thought on the point when a texture becomes something higher up the musical foodchain?

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|