|

Ian Pace

|

|

« on: 11:41:45, 16-09-2007 » |

|

A thought following on from the ignorance thread: in response to my pocket guide to remembering which sixth is which: German - like dominant seventh

Italian - like dominant seventh without the fifth

French - pair of major thirds with a whole tone between them

Neapolitan sixth - simply a major sixth with, for its lowest pitch, the third degree of the scale beginning on the flattened supertonic. Member Cassidy writes: (It's also a crap explanation of augmented 6ths, as it focuses on intervallic relationships rather than a) voice leading and b) chord function -- the pivotal issues are the crucial VL tendencies of each of the scale degrees (most importantly, #4-5 and b6-5, moving in contrary motion) and the built-in harmonic motion towards the dominant. It's tonal harmony -- it's all about function; intervals (at least as abstract objects) are irrelevant.) But I wonder (and genuinely don't have a firm answer to this), whether the latter clause is necessarily true specifically in the case of the French sixth? Of course it can be, and often was, used essentially for a functional harmonic purpose, but this particular chord, precisely because of its intervallic properties, has such a distinctive harmonic colouration and polyvalency of harmonic implication, comprised as it is of intervals formed from whole tones, that does it not anticipate some degree of emancipation of harmonic colour from tonal function, such as obviously became the case in late 19th/early 20th century French music in particular (also anticipated in the music of Liszt, who used this and other intervals (especially over-using the diminished seventh) for the purposes of creating tonal and harmonic ambiguity as part of his exoticising tendencies)? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

autoharp

|

|

« Reply #1 on: 12:13:34, 16-09-2007 » |

|

Ian - your second sentence is long and loaded ! I think an example would help. I've often found that the problem with some (much?) harmonic analysis is that it is confused, wrong-headed and may well have nothing to do with what the composer is thinking. A good example of such a can of worms can be found at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tristan_chordFortunately Italian, French and German sixths are mostly clearcut and I'd agree with Aaron's point. But the legit view is seldom 100% correct . . . And the Australian 6th ? |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #2 on: 12:34:35, 16-09-2007 » |

|

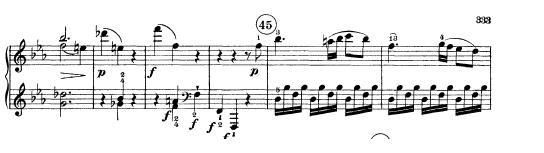

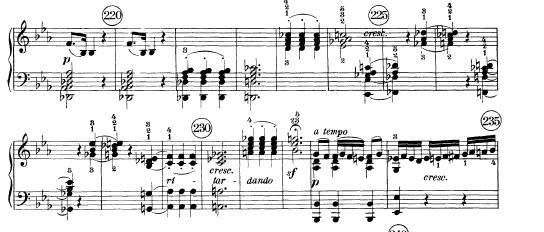

Ian - your second sentence is long and loaded ! I think an example would help. Just really saying (or, rather, offering as a hypothesis) that the French sixth anticipates whole-tone harmonies, and that its intervallic properties are relevant in this case. Trying to think of a good example (preferably a late 18th/early 19th one) that exemplifies what I mean - will try and come up with one later. I've often found that the problem with some (much?) harmonic analysis is that it is confused, wrong-headed and may well have nothing to do with what the composer is thinking. Well, is 'what the composer is thinking' necessarily the bottom line? I wonder if the problem comes from a continuing lack of consensus as to whether to privilege the vertical or horizontal in musical analysis - in some music, placing big chord symbols at as many vertical points as possible can suggest that the music is much more clunky than it actually sounds.... The comparison with Beethoven Op. 31 No. 3 there is very interesting - despite Beethoven's not giving the harmony the same duration or degree of emphasis that Wagner does, nonetheless he resolves onto a diminished seventh then just repeats the same thing up the octave, then back down and a whole tone raised, before eventually resolving onto the dominant of B-flat via an Italian sixth* (see below; Beethoven doesn't repeat this in the recapitulation, but does something arguably more tonally ambiguous in the coda, also included). Whereas Wagner moves onto a clear dominant seventh in the next bar, in such a way that enables the dissonant pitches (save arguably for the B in the tenor part) to be heard primarily as chromatic passing notes, rather than anything significantly undermining the role of harmonic function. Wagner has a clear goal, ultimately reinforcing the most fundamental component of tonal harmony, the dominant seventh, whereas Beethoven is happy to musically 'wander' without any obvious goal - this was the aspect of Beethoven that Liszt developed far more than did Wagner. The notion of the Tristan chord, as used by Wagner, undermining the sense of tonality, I find hard to really buy. Beethoven Piano Sonata Op. 31 No. 3, first movement, bars 32-46.   bars 219-234.  * Afterthought - the harmony at bar 42 might be heard as a German sixth, depending in part on whether the pedal sustains the D-flat through onto the second beat. It all depends really if one hears the there-fragmenting upper part as still intrinsic to the overall harmony or not? Maybe this is a case where such reductive vertical analysis hardly does justice to what is going on? |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 12:53:33, 16-09-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Chafing Dish

Guest

|

|

« Reply #3 on: 13:21:28, 16-09-2007 » |

|

I wonder if the problem comes from a continuing lack of consensus as to whether to privilege the vertical or horizontal in musical analysis - in some music, placing big chord symbols at as many vertical points as possible can suggest that the music is much more clunky than it actually sounds....

Yes, the placement of harmonic symbols can be misleading, but it is one tool in understanding harmony that overlooks the horizontal. It takes an effort to convince students that this isn't a clunkifier. Wagner has a clear goal, ultimately reinforcing the most fundamental component of tonal harmony, the dominant seventh, whereas Beethoven is happy to musically 'wander' without any obvious goal - this was the aspect of Beethoven that Liszt developed far more than did Wagner. The notion of the Tristan chord, as used by Wagner, undermining the sense of tonality, I find hard to really buy. We don't just look at the first instance of the chord, but observe that it behaves in many different ways throughout the opera, far more radically than can be explained by traditional harmonic theories. That's why Ernst Kurth's book isn't called Die Romantische Harmonik und ihre Krise in Beethoven's Es-dur Sonate. Though the first arrival in the prelude is a deceptive cadence in a minor (sort of), nobody reasonable tries to argue that the prelude really stands in A. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #4 on: 13:42:04, 16-09-2007 » |

|

Wagner has a clear goal, ultimately reinforcing the most fundamental component of tonal harmony, the dominant seventh, whereas Beethoven is happy to musically 'wander' without any obvious goal - this was the aspect of Beethoven that Liszt developed far more than did Wagner. The notion of the Tristan chord, as used by Wagner, undermining the sense of tonality, I find hard to really buy. We don't just look at the first instance of the chord, but observe that it behaves in many different ways throughout the opera, far more radically than can be explained by traditional harmonic theories. OK - but just sticking with the prelude on its own for now, would you say it operates as a highly enrichened development of tonal harmony, with copious use of extravagant dissonant harmonies, or one that actually undermines the goal-oriented aspects of that very tonal system (that is, if it ever existed in such a pure form, which is of course questionable)? Tonal closure is forever displaced (as it is in various earlier composers, for example Schumann, though not to quite the same degree and with the same harmonic opulence), but still remains a powerful underlying presence throughout the prelude; in this respect I wonder if such an inexorable sense of direction is possibly more intrinsic to this music of Wagner than in some places in Beethoven, or in Liszt, or in Debussy (or in some other Wagner, including the Magic Fire music)? That's why Ernst Kurth's book isn't called Die Romantische Harmonik und ihre Krise in Beethoven's Es-dur Sonate. No, but others (including Adorno) have examined that sort of aspect of Beethoven, introducing moments tending towards the spatial within an otherwise harmonically directional context (Adorno possibly makes somewhat too much of them, though). Though the first arrival in the prelude is a deceptive cadence in a minor (sort of), nobody reasonable tries to argue that the prelude really stands in A. What I'm never really sure about is whether the long passage that is essentially in A (and has that key signature) is strengthened and/or consolidated by the earlier presence of that opening incomplete cadence and its continuations - so that it provides a delayed partial resolution? What do you reckon? |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 14:06:02, 16-09-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

roslynmuse

|

|

« Reply #5 on: 14:11:06, 16-09-2007 » |

|

Is 'what the composer is thinking' necessarily the bottom line?

I'm inclined to think it is - even if it isn't necessarily the only line. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Reiner Torheit

|

|

« Reply #6 on: 14:54:06, 16-09-2007 » |

|

Wagner has a clear goal, ultimately reinforcing the most fundamental component of tonal harmony, the dominant seventh, whereas Beethoven is happy to musically 'wander' without any obvious goal - this was the aspect of Beethoven that Liszt developed far more than did Wagner. The notion of the Tristan chord, as used by Wagner, undermining the sense of tonality, I find hard to really buy.

The "perpetrator" of this notion was no less a personage than Ferrucio Busoni. He inveighed against Wagner's "malign" influence in this matter so fiercesomely that he refused to even name Wagner in his lectures, referring to "Herr W" or simply "that German man". He held Wagner personally responsible for the "calamity" of the collapse of tonality as a compositional structure, and felt so strongly on the matter that he relocated to Vienna and Berlin to lecture on the topic in opposition to Schoenberg (whom he apparently like personally, calling him "misguided" rather than "wrong"). The "Tristan Chord" was Busoni's especial bugbear. I am not saying this is all correct simply because Busoni said so... but it seems rash to dismiss the idea out of hand, given his historical position in the post-Wagnerian aftermath. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

"I was, for several months, mutely in love with a coloratura soprano, who seemed to me to have wafted straight from Paradise to the stage of the Odessa Opera-House"

- Leon Trotsky, "My Life"

|

|

|

|

increpatio

|

|

« Reply #7 on: 18:40:49, 16-09-2007 » |

|

German - like dominant seventh

Italian - like dominant seventh without the fifth

French - pair of major thirds with a whole tone between them

Neapolitan sixth - simply a major sixth with, for its lowest pitch, the third degree of the scale beginning on the flattened supertonic. Bah. A real explanation would relate them to national characteristics. (Interesting thread; I don't have anything constructive to add at the moment though). |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

roslynmuse

|

|

« Reply #8 on: 19:00:30, 16-09-2007 » |

|

German - like dominant seventh

Italian - like dominant seventh without the fifth

French - pair of major thirds with a whole tone between them

Neapolitan sixth - simply a major sixth with, for its lowest pitch, the third degree of the scale beginning on the flattened supertonic. Bah. A real explanation would relate them to national characteristics. (Interesting thread; I don't have anything constructive to add at the moment though). ie German - dominant, Italian - not quite as dominant as the Germans, French - avoid dominance at any price, Neapolitan - simple.  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #9 on: 19:27:51, 16-09-2007 » |

|

Wagner has a clear goal, ultimately reinforcing the most fundamental component of tonal harmony, the dominant seventh, whereas Beethoven is happy to musically 'wander' without any obvious goal - this was the aspect of Beethoven that Liszt developed far more than did Wagner. The notion of the Tristan chord, as used by Wagner, undermining the sense of tonality, I find hard to really buy. We don't just look at the first instance of the chord, but observe that it behaves in many different ways throughout the opera, far more radically than can be explained by traditional harmonic theories. OK - but just sticking with the prelude on its own for now, would you say it operates as a highly enrichened development of tonal harmony, with copious use of extravagant dissonant harmonies, or one that actually undermines the goal-oriented aspects of that very tonal system (that is, if it ever existed in such a pure form, which is of course questionable)? Tonal closure is forever displaced (as it is in various earlier composers, for example Schumann, though not to quite the same degree and with the same harmonic opulence), but still remains a powerful underlying presence throughout the prelude; in this respect I wonder if such an inexorable sense of direction is possibly more intrinsic to this music of Wagner than in some places in Beethoven, or in Liszt, or in Debussy (or in some other Wagner, including the Magic Fire music)? That's why Ernst Kurth's book isn't called Die Romantische Harmonik und ihre Krise in Beethoven's Es-dur Sonate. No, but others (including Adorno) have examined that sort of aspect of Beethoven, introducing moments tending towards the spatial within an otherwise harmonically directional context (Adorno possibly makes somewhat too much of them, though). Though the first arrival in the prelude is a deceptive cadence in a minor (sort of), nobody reasonable tries to argue that the prelude really stands in A. What I'm never really sure about is whether the long passage that is essentially in A (and has that key signature) is strengthened and/or consolidated by the earlier presence of that opening incomplete cadence and its continuations - so that it provides a delayed partial resolution? What do you reckon? I find this intensely interesting (perhaps Busoni - for whom my respoect remains immense - might have opined that I find it unhealthily so!). The " Tristan chord" - which you cite above from its much earlier appearance in that Beethoven sonata - was not "new" when Beethoven used it either, of course - but what really bothers me is this conept that Wagner somehow achieved some kind of historical importance by "undermining" tonal stability by the use of this chord in Tristan. Now this is not to undermine Wagner's achievement here but I think that, to begin with, tonal stability and the prevalence of the tonal centre was perhaps more effectively undermined by Wagner in Act III of the same work as by his use of that chord alone; next, we have to bear in mind that earlier composers have used the "Tristan chord". Lastly, however, I would return to this notion of "undermining" tonal stability. Delayed resolution and absence of tonal closure do not of themselves "undermine" tonality itself; rather the opposite, it seems tome, for they heighten the vaildity of tonal relationships. I think that, in Tristan and in parts of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung, what wagner actually did was to expand tonal horizons rather than undermine anything; the idea of "undermining" suggests something negative, whereas Wagner's widening of the possibilities of tonality and tonal relationships was very positive, so that, by the time we get to Schönberg's Kammersymphonie Nr. 1 some half-century after Tristan, the vocabulary of tonal inter-relationships had become immense by comparison to what is had been at the time of Schumann's death - all manner of levels of tension and non-tension had entered into the consciousness, without tonality per se being in any sense overthrown thereby. Of course, I do not seek to overplay Wagner's personal input into this, for other composers got into it as well, although few if any others pursued the art of delayed resolution on quite the same scale as he did. Sorry, folks - must get off me hobby-horse (and maybe get me coat, too)! - it's all Ian's fault for raising and developing this (to me) fascinating subject area... Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #10 on: 19:36:04, 16-09-2007 » |

|

A thought following on from the ignorance thread: in response to my pocket guide to remembering which sixth is which: German - like dominant seventh

Italian - like dominant seventh without the fifth

French - pair of major thirds with a whole tone between them

Neapolitan sixth - simply a major sixth with, for its lowest pitch, the third degree of the scale beginning on the flattened supertonic. OK - now recalling your necessarily forceful recent diatribe against the absurdities of a certain musicologist on another thread on this forum, should we assume that a German sixth is a male device and a French sixth a female one?(!)... I know that what I'm about to write here ought to take us all back to the ignorance thread, but I, like Sir Richard III, have long had a difficulty in remembering the differences between these various sixths. I've always wondered in any case if there's some kind of sinister racist undertone to these descriptions of sixths; Richard has not yet to reveal to us all what a Welsh sixth is and I have no idea what constitutes a Scottish one (unless it's one that simply snaps upon execution). And, given their countries' long established history in European music, where are the Spanish and the Portuguese sixths? Hmmm - time to go back to school, methinks!... Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Chafing Dish

Guest

|

|

« Reply #11 on: 20:40:06, 16-09-2007 » |

|

This is all available in elementary harmony textbooks. What they usually leave out, though, is where the terms actually come from. All aug6 chords contain the flatted submediant (b6) in the bass and the raised subdominant (#4) in another voice, usually the highest. These then are expected to resolve outward to the dominant (5). The Italian adds the tonic pitch (1), and in four part writing this pitch is generally doubled. When the harmony passes on to the dominant (as is expected), one of these tonic notes must go to the leading tone (7). The other, if present, can move to the supertonic (2). The French sixth chord adds the supertonic pitch as well, which stays put into the dominant harmony. The German sixth chord adds the flatted mediant instead of supertonic. Since this note is a perfect fifth above the bass, however, it usually hangs around as a suspension into the dominant to avoid the sensation of parallel fifths. Alternatively, and for the same reason, this b3 can arrive early on the supertonic as a kind of anticipation. Note that in that moment of anticipation, the kraut has briefly morphed into a frog. Old Walter Piston even distinguished between two German sixth chords, the one with the flatted mediant he called German, and the one with the raised supertonic he called "Swiss" -- as far as I know, no one took him up on this idea. But in a nutshell, the German reflects a tendency for the tone in question to resolve to the natural supertonic, while the Swiss spelling (of an identical-sounding chord, mind you) accommodates a tendency to the natural mediant, i.e., when the bass moves from b6 to 5, the #2 moves first to 3, making a six-four chord (double suspension) on the dominant. The Swiss spelling would be more common in major mode and the German more common in minor. Both German and French can (hypothetically) omit the tonic note, but I can only think of one instance in music literature where this happens. True anoraks can think of a dozen, I'm sure. Finally, the Neapolitan sixth chord is not an augmented sixth chord at all, but an anteater a tapir. In minor mode, this chord is like a first-inversion supertonic harmony (which is normally diminished 4-b6-2) whose "root" has been flatted to form a more consonant (major 4-b6-b2) sonority. What it makes up in pleasantness it lacks in melodic smoothness, however: the b2 has trouble resolving properly since it typically tends toward 1 (a half-step away), and yet Neapolitan harmony is, like the harmony for which it substitutes (ii), a pre-dominant harmony, so that b2 frequently makes the rather striking move straight to the leading tone (an interval of a diminished third). If b2 does go to 1 first, then once again you have a suspension. In major mode, the Neapolitan is even more striking, since it has two notes outside the key, and we generally consider it in those instances as being "borrowed" from the minor mode. The Neapolitan only "resolves" to tonic when one thinks of it, like the jazz community on occasion, as a substitute for the dominant rather than as a fancy pre-dominant. As for national characteristics, I don't see a particularly convenient or compelling way to show that that is very interesting or relevant. That is, until you read some of the more outrageous mnemonic devices that theory teachers come up with! |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

increpatio

|

|

« Reply #12 on: 21:19:29, 16-09-2007 » |

|

We have been given "the talk". Thanks; will take me an evening to digest I think. |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Chafing Dish

Guest

|

|

« Reply #13 on: 21:39:09, 16-09-2007 » |

|

It takes most University of Illinois graduate students an entire semester, even after they have consumed a semester more as undergraduates. So an evening is quite an impressive time-frame, inc!

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

time_is_now

|

|

« Reply #14 on: 22:06:26, 16-09-2007 » |

|

Finally, the Neapolitan sixth chord is not an augmented sixth chord at all, but an anteater a tapir. In minor mode, this chord is like a first-inversion supertonic harmony (which is normally diminished 4-b6-2) whose "root" has been flatted to form a more consonant (major 4-b6-b2) sonority. What it makes up in pleasantness it lacks in melodic smoothness, however: the b2 has trouble resolving properly since it typically tends toward 1 (a half-step away), and yet Neapolitan harmony is, like the harmony for which it substitutes (ii), a pre-dominant harmony, so that b2 frequently makes the rather striking move straight to the leading tone (an interval of a diminished third). If b2 does go to 1 first, then once again you have a suspension. Not really, since the scale degree 1 is landed on at the same time as the bass moves from scale degree 4 to scale degree 5 - is that still called a suspension (maybe it is, I'm more than a bit rusty on tonal harmony)? Anyway, wouldn't it be more normal to move from the Neapolitan harmony to a 6/4 harmony over the dominant note in the bass, and thence to 5/3 (chord V) cadencing on to chord I? Sorry. That probably wasn't much help. Aside from all that I agree with Aaron that describing a German sixth (etc.) as 'like a dominant seventh' begs just about every important question going, since the 2 most obvious difference are (1) that its root is not the dominant at all but the flattened 6th scale degree (which then falls to the dominant by step, without exception as far as I'm aware); (2) that it's only enharmonically equivalent to a seventh chord, since it spells itself differently, i.e. C-E-G-Bb is a dominant seventh chord in F major (or indeed in F minor, too) whereas C-E-G-A# is a German sixth in E minor (or E major, I suppose). Oh, and 'like dominant seventh without the fifth' isn't much help either: who ever said a dominant seventh needs to contain the fifth?  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

The city is a process which always veers away from the form envisaged and desired, ... whose revenge upon its architects and planners undoes every dream of mastery. It is [also] one of the sites where Dasein is assigned the impossible task of putting right what can never be put right. - Rob Lapsley

|

|

|

|