|

Sydney Grew

Guest

|

|

« Reply #90 on: 13:07:32, 03-06-2007 » |

|

I have thought about this issue (emotions verses intellectual reasoning. . . .) We do not think the best composers aim to express either emotions or intellectual matters. No, what they want to create is a beautiful work. Sometimes - indeed often - our emotions are stirred when we hear beautiful music, but that stirring is not the purpose of the music - the beauty is. Similarly, the purpose of a piece of music is never primarily an intellectual stimulation. The concern of true Art is always and only expression of the beautiful. Madame will know the French phrase "Art for Art's sake"! |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

trained-pianist

|

|

« Reply #91 on: 13:16:32, 03-06-2007 » |

|

Thank you Mr Sidney Grew, I like your post very much. May be I was influenced too much by my upbringing. Where I come from the idea was to use art for propaganda reasons or to promote specific social ideas (the ideas themselves were usually nobel and good). But Art for Art's sake was scorned and looked down.

I like your point very much. Thank you again.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #92 on: 02:05:33, 25-07-2007 » |

|

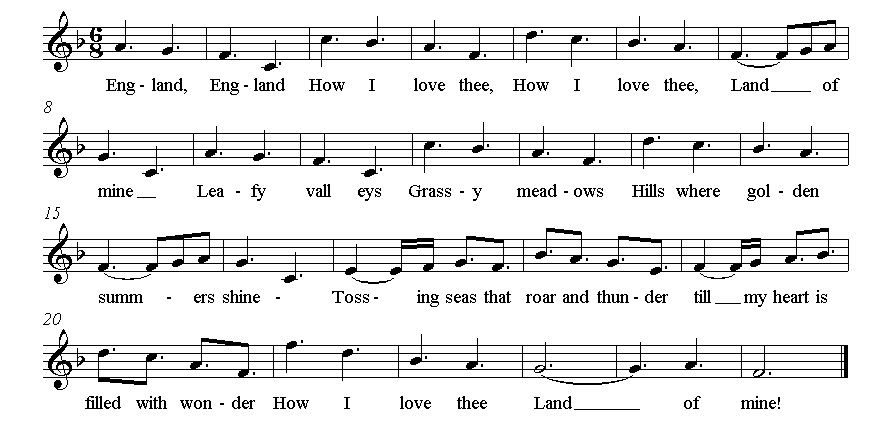

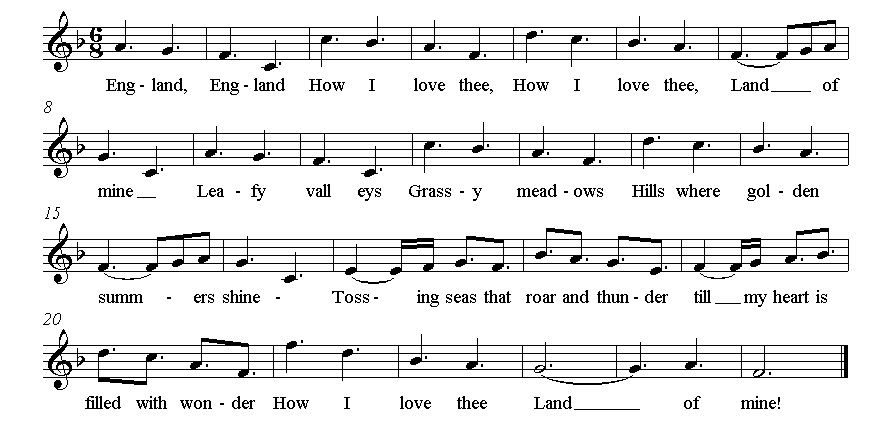

Came across something in the library today that I have to share - in amongst one of those library volumes that bind lots of different scores together, I encountered an adaptation by Stuart Young, published by Augener, of the hymn-like melody in the last movement of Brahms's Piano Sonata in F minor Op. 5. It's for voice and piano, transposed into F - I've just copied some of the vocal part here - was about to roar with laughter until I realised that the BL is not the place for doing that. Will it ever be possible to hear it in the same way again?   (mind you, was a nice break from studying the full score of that real turkey the Triumphlied!) |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #93 on: 08:13:26, 25-07-2007 » |

|

Well, I don't find Brahms at all emotionally reticent; however, as a personality he was distrustful of fleeting impulse (let alone idle sentiment), or that which seems somehow irrationally motivated (in this sense he was hugely different in temperament from Berlioz, Schumann or Liszt, say). The emotional content is no less pronounced, just that it tends to operate in a deeper and more thoroughgoing manner. Could anyone tell me that, say, the Violin Concerto is anything other than a deeply heartfelt work?

Well, I for one certainly couldn't - but then I wouldn't, anyway. Where is the "emotional reticence" in the three early piano sonatas (which, for all that they occur so soon in Brahms's output, show remarkably little sign of immaturity. The piano quintet "emotionally reticent"? The C minor piano quartet? The Double Concerto? The Piano Trio in C major, whose first movement in particular seems almost fit to burst? Well, not for me, that's for sure! Your penultimate sentence encapsulates the situation perfectly - for me, at any rate. Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #94 on: 08:20:50, 25-07-2007 » |

|

Came across something in the library today that I have to share - in amongst one of those library volumes that bind lots of different scores together, I encountered an adaptation by Stuart Young, published by Augener, of the hymn-like melody in the last movement of Brahms's Piano Sonata in F minor Op. 5. It's for voice and piano, transposed into F - I've just copied some of the vocal part here - was about to roar with laughter until I realised that the BL is not the place for doing that. Will it ever be possible to hear it in the same way again?   (mind you, was a nice break from studying the full score of that real turkey the Triumphlied!) Maybe you should send this wonderful piece of - er - (lost for words right now) - to the editor, or better still the probably non-existent music critic, of that rag This England that was discussed in these hallowed pages a few days ago; I'm sure that a reproduction of this work by the well-known English pastoralist John Bramley as adapted by Mr Young would go down well in that esteemed journal. Yes, it WILL be possible to hear it "the same way again"; muss es sein - es muss sein! Any effort required to banish this temporarily amusing yet permanently appalling excrescence from one's mind will be worth making; the best way is probably to go to the nearest piano and play the original, although I accept that "we" can't all do that... Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #95 on: 08:55:22, 25-07-2007 » |

|

Well, I don't find Brahms at all emotionally reticent; however, as a personality he was distrustful of fleeting impulse (let alone idle sentiment), or that which seems somehow irrationally motivated (in this sense he was hugely different in temperament from Berlioz, Schumann or Liszt, say). The emotional content is no less pronounced, just that it tends to operate in a deeper and more thoroughgoing manner. Could anyone tell me that, say, the Violin Concerto is anything other than a deeply heartfelt work?

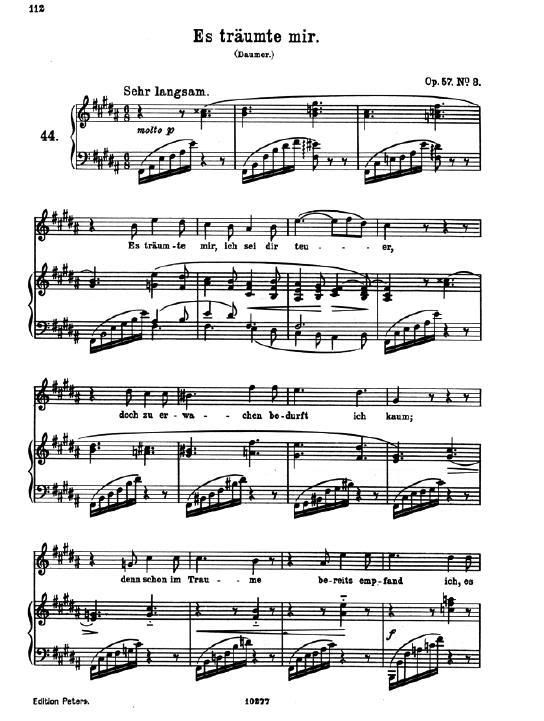

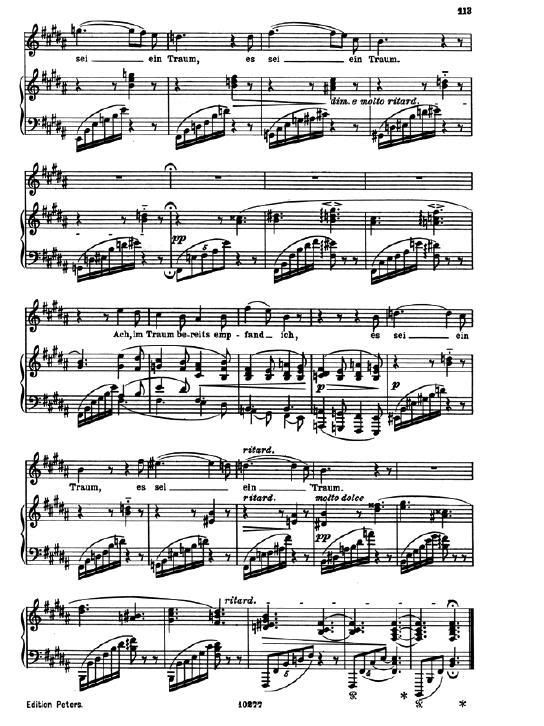

Well, I for one certainly couldn't - but then I wouldn't, anyway. Where is the "emotional reticence" in the three early piano sonatas (which, for all that they occur so soon in Brahms's output, show remarkably little sign of immaturity. The piano quintet "emotionally reticent"? The C minor piano quartet? The Double Concerto? The Piano Trio in C major, whose first movement in particular seems almost fit to burst? Well, not for me, that's for sure! Your penultimate sentence encapsulates the situation perfectly - for me, at any rate. Also, there are numerous works of Brahms that are unusual in terms of what one might identify as more generalised qualities of his output. Certainly the early Hamburg works show a composer engaging with a variety of idioms - a type of tongue-in-cheek Lisztian virtuosity in the F# minor Sonata, 'characteristic music' in the Schumann Variations, exoticism in the Ballades, Weberian romanticism in the Four Songs Op. 17 for choir, two horns and harp, the narrative lieder cycle in the Die Schöne Magelone, and so on. But there are all sorts of other idiosyncratic works from later - an incredibly diverse approach to appropriating genres within the waltz format in the two sets of Liebeslieder, charged eroticism in the Lieder und Gesänge von G.F. Daumer, Op. 57, nationalist triumphalism in the Triumphlied, extraordinarily haunting (and bleak) use of orchestral colour in Nänie, a love of colour for its own sake in the orchestrated versions of three of the Ungarische Tänze, and so on. I can see why some find the First String Quartet Op. 51 No. 1, somewhat laboured, with every group of a few notes exhaustively developed as much as one could, though still love it. But Brahms is still a multifarious composer, and was throughout much of his life. |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 09:04:00, 25-07-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #96 on: 10:04:21, 25-07-2007 » |

|

Well, I don't find Brahms at all emotionally reticent; however, as a personality he was distrustful of fleeting impulse (let alone idle sentiment), or that which seems somehow irrationally motivated (in this sense he was hugely different in temperament from Berlioz, Schumann or Liszt, say). The emotional content is no less pronounced, just that it tends to operate in a deeper and more thoroughgoing manner. Could anyone tell me that, say, the Violin Concerto is anything other than a deeply heartfelt work?

Well, I for one certainly couldn't - but then I wouldn't, anyway. Where is the "emotional reticence" in the three early piano sonatas (which, for all that they occur so soon in Brahms's output, show remarkably little sign of immaturity. The piano quintet "emotionally reticent"? The C minor piano quartet? The Double Concerto? The Piano Trio in C major, whose first movement in particular seems almost fit to burst? Well, not for me, that's for sure! Your penultimate sentence encapsulates the situation perfectly - for me, at any rate. Also, there are numerous works of Brahms that are unusual in terms of what one might identify as more generalised qualities of his output. Certainly the early Hamburg works show a composer engaging with a variety of idioms - a type of tongue-in-cheek Lisztian virtuosity in the F# minor Sonata, 'characteristic music' in the Schumann Variations, exoticism in the Ballades, Weberian romanticism in the Four Songs Op. 17 for choir, two horns and harp, the narrative lieder cycle in the Die Schöne Magelone, and so on. But there are all sorts of other idiosyncratic works from later - an incredibly diverse approach to appropriating genres within the waltz format in the two sets of Liebeslieder, charged eroticism in the Lieder und Gesänge von G.F. Daumer, Op. 57, nationalist triumphalism in the Triumphlied, extraordinarily haunting (and bleak) use of orchestral colour in Nänie, a love of colour for its own sake in the orchestrated versions of three of the Ungarische Tänze, and so on. I can see why some find the First String Quartet Op. 51 No. 1, somewhat laboured, with every group of a few notes exhaustively developed as much as one could, though still love it. But Brahms is still a multifarious composer, and was throughout much of his life. Agreed - and expressed with more elegance and detail than my two-pennarth. The quartet I have a problem with (though not that much of one, admittedly) is the B flat, Op. 67, which strikes me as rather dull and workmanlike compared to all of Brahms's other chamber works - in fact, to me, it tends to epitomise all those things about Brahms that one hears from those who don't get close to his work and which, for the most part, I cannot perceive! Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 13:44:12, 07-08-2007 by ahinton »

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #97 on: 12:27:53, 07-08-2007 » |

|

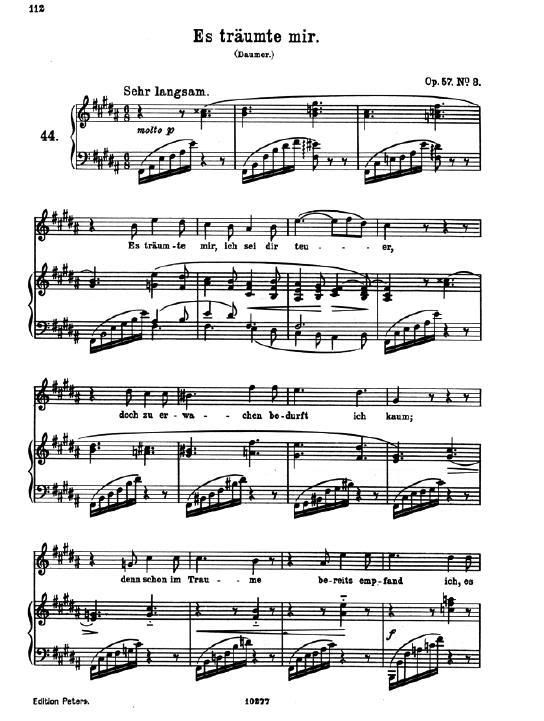

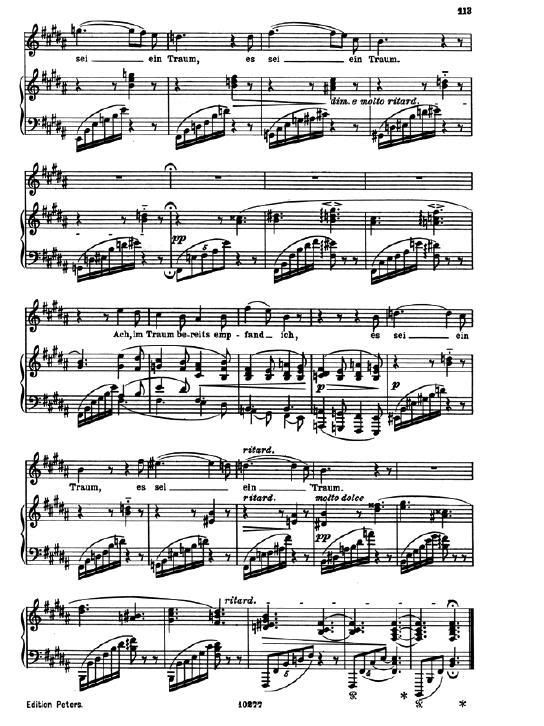

Brahms has come up in the 'Learning to Love' thread, wanted to post a particular favourite song, from the Op. 57 set.   |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #98 on: 12:34:10, 07-08-2007 » |

|

Ollie commented on not liking the 'brown' school of Brahms performance on that other thread, wanted to recommend to him these recordings, which I think he'll like:  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #99 on: 12:45:16, 07-08-2007 » |

|

Thanks Ian, I'll have a look at those. I'm listening to another very non-brown Brahms recording at the moment although I'd better not say who's conducting...  |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #100 on: 12:46:55, 07-08-2007 » |

|

Weingartner is the only conductor who worked with Brahms of whom we have recordings. By all accounts, his approach was extremely different to that of Hans von Bülow and Fritz Steinbach, though it maybe shared some similarities with the conducting of Hans Richter.

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #101 on: 17:32:47, 07-08-2007 » |

|

Brahms has come up in the 'Learning to Love' thread, wanted to post a particular favourite song, from the Op. 57 set.   Many thanks for sharing this with us - a lovely thing indeed! Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

ahinton

|

|

« Reply #102 on: 17:58:22, 07-08-2007 » |

|

Weingartner is the only conductor who worked with Brahms of whom we have recordings. By all accounts, his approach was extremely different to that of Hans von Bülow and Fritz Steinbach, though it maybe shared some similarities with the conducting of Hans Richter.

This is certainly true as far as I know. Moving forward somewhat in time, however, this "brown" Brahms that bothers some people is, I think, without doubt down to performance inadequacies rather than anything to do with the musical content itself or the way in which Brahms cast it. That composer whose name I dare not speak mentioned this phenomenon and, whilst some of Brahms was not exactly his favourite cup of tea, he had been greatly enthused by Toscanini conducting Brahms for the sheer translucent clarity that he brought to his orchestral music, adding, however, that, on reflection, he'd brought no such thing to it after all because it was already there in Brahms's writing. This "problem", I think, has it roots in performing "traditions" that can grow up independently of the music itself and (as in the case of certain Brahms works) risk misleading listeners as to how that music is meant to sound. By a similar token, Malcolm MacDonald once gently but firmly took to task those who criticised certain (usually Russian) conductors for "exaggerating" certain dynamics in Tchaikovsky by reminding them that those extreme dynamics are in Tchaikovsky's score. But to return to Brahms; there is another was to come at this, too - as Ives did when he wrote To think hard and deeply and to say what is thought, regardless of consequences, may produce a first impression either of great translucence or great muddiness, but in the latter case there may be hidden possibilities. Some accuse Brahms's orchestration of being muddy. This may be a good name for a first impression of it. But if it should seem less so, he might not be saying what he thought. The mud may be a form of sincerity which demands that the heart be translated, rather than handed around through the pit. A clearer scoring might have lowered the thought.Now I have to admit that I don't see Ives to Ives with him here, in that I do not as a rule find Brahms's orchestration inherently muddy in the first place, but he nevertheless had a point and an interesting thought there, I think. I do, however, believe that "brown Brahms" is an unfortunate phenomenon that has tended to emanante principally from those who are tempted to see in his work something of German soil in the "muddy" sense. What do you think about that? Best, Alistair |

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

oliver sudden

|

|

« Reply #103 on: 18:11:31, 07-08-2007 » |

|

This whole matter of taste thing is of course a particular problem when the transmission of a work (or even of one's whole impression of a composer) passes through so many stages each with their associated confusions. I find Brahms's scoring pretty clear myself, on the page and in the performances which do the most for me; like much other music (Schumann as well) it often doesn't sound that way when the balance between the orchestral choirs is upset by an overly enthusiastic brass section or, well, it's just my opinion, a Karajan-type fattening of the string sound. (Sorry, he's a bugbear of mine. Maybe I'll get over it. I just have great problems convincing myself that he could actually hear harmony.)

But yes, I've seen Brahms described as 'that incomparable master of greys and browns', I think in a programme note on my shelf somewhere. (I'll dig it up when I'm back home.) I suppose that's not essentially any different from, for example, being an ardent fan of Bach's monumental side, which as far as I'm concerned is almost invariably something of our making not his. And I suppose if a listener derives pleasure from that sort of thing, why shouldn't they?

|

|

|

|

|

Logged

Logged

|

|

|

|

|

Ian Pace

|

|

« Reply #104 on: 18:26:04, 07-08-2007 » |

|

This whole matter of taste thing is of course a particular problem when the transmission of a work (or even of one's whole impression of a composer) passes through so many stages each with their associated confusions. I find Brahms's scoring pretty clear myself, on the page and in the performances which do the most for me; like much other music (Schumann as well) it often doesn't sound that way when the balance between the orchestral choirs is upset by an overly enthusiastic brass section or, well, it's just my opinion, a Karajan-type fattening of the string sound. (Sorry, he's a bugbear of mine. Maybe I'll get over it. I just have great problems convincing myself that he could actually hear harmony.) That fattening did also go on in part in Brahms's lifetime as well (his symphonies being played by the much larger Vienna Philharmonic as well as the Meiningen Court Orchestra, and lots of other large orchestras), and it's by no means clear that he definitely opted for the thinner string sound (personally, I tend towards the opinion that he was quite well-disposed towards it specifically in the Meiningen case, but there's plenty of other evidence - it's very hard to make a conclusive case). Be wary of the possibility that what seems clear to oneself in the music may simply entail the projection of a later neo-classical aesthetic onto it. But yes, I've seen Brahms described as 'that incomparable master of greys and browns', I think in a programme note on my shelf somewhere. (I'll dig it up when I'm back home.) I suppose that's not essentially any different from, for example, being an ardent fan of Bach's monumental side, which as far as I'm concerned is almost invariably something of our making not his. And I suppose if a listener derives pleasure from that sort of thing, why shouldn't they? Well, there are plenty of contemporary reports from Brahms's time describing performances in similar terms, including of those he was either involved with or clearly approved of. I don't have references with me right here at the moment, but will at some point dig them out. As far as Toscanini is concerned, his conducting is much closer to that of Weingartner than that of Steinbach, from what we know of either. But I would say on balance there is considerably more evidence that Brahms was inclined towards the Steinbach tradition (very much more flexible than the more strict Weingartner). Gunther Schuller argues for the unequivocal superiority of the Weingartner/Toscanini approach in his book The Compleat Conductor, but without much in the way of documentary evidence - this is mostly about Schuller's own personal preferences (nothing wrong with that, of course) rather than anything that is particularly historically grounded. I am very wary when people make quite exalted claims about certain performing traditions being at odds with the composer's intentions ('misleading listeners as to how that music is meant to sound', for example) without having investigated the matter historically. |

|

|

|

« Last Edit: 18:48:19, 07-08-2007 by Ian Pace »

|

Logged

Logged

|

'These acts of keeping politics out of music, however, do not prevent musicology from being a political act . . .they assure that every apolitical act assumes a greater political immediacy' - Philip Bohlman, 'Musicology as a Political Act'

|

|

|

|